- Posted on 9 Jul 2025

This article appeared in Crikey on July 9 2025.

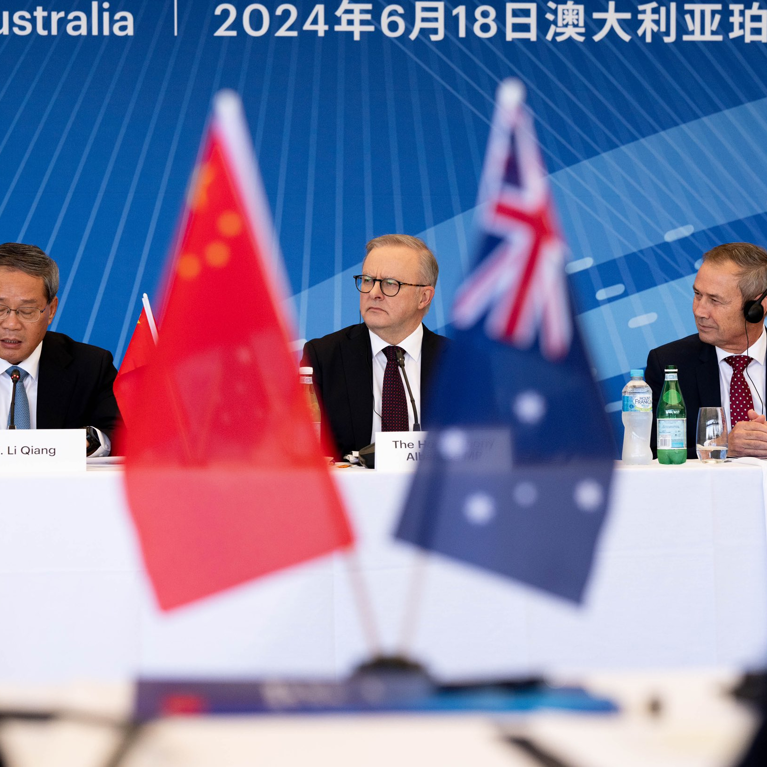

If you’re looking for an example of how our media can turn a good story into a bad one, simply pay attention to how Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s forthcoming visit to China is being reported.

A journalist from The Australian asked Barnaby Joyce, a ‘Coalition heavyweight’, whether it was not good to ‘make friends with China’. Joyce said we should do so, ‘but not at the expense of the US’, and that Albanese was playing a ‘very dangerous’ game. Criticising Albanese’s recent speech inspired by John Curtin, an op-ed by Greg Sheridan in the same newspaper was titled ‘Washington will not be impressed by Anthony Albanese’s Curtin call… but Beijing will lap it up’.

Sky News then outperformed The Australian by showing us that a good story is in fact a bad story. Speaking about Albanese’s imminent visit to China, Sharri Markson remarks with incredulity, ‘This is truly astonishing that he is about to meet President Xi for the fourth time, while he still hasn’t managed to secure a single meeting with the US president … This is deeply worrying.’

The framing of these stories seems to follow the logic of ‘it goes without saying’. That is, a story about diplomatic relations between Australia and China is necessarily a story about Australia and the US, and a story about Australia-US relations is necessarily a story about Australia and China.

In each case, our media and Coalition politicians seem to imagine Australia as a child whose parents’ protracted divorce proceedings have ended in a messy shared custody arrangement. Caught between a tempestuous dad and a needy mum (you can choose which is which), the child cowers, fearing every word spoken between the parents like a loaded gun. Anxious not to displease either parent, the child can’t decide whether to spend the holidays at mum’s or go on a trip with dad instead.

You’d be wrong in assuming it’s just the Murdoch media that likes to infantilise Australia in this way. A recent headline in The Age sums it up: ‘Between Xi and Trump, can PM afford to be ‘relaxed and comfortable’’?

Media stories and public commentaries from some one-track-minded policy-thinkers and politicians are often peppered with superficial analyses, interpreting the government’s every move as an attempt to ‘send a signal to Beijing’ or to ‘reassure Washington’. This lazy and shallow analysis is symptomatic of what’s wrong with much foreign policy thinking in this country.

Commenting on Albanese’s difficulty in setting up a meeting with Trump, and on Xi Jinping’s conjectured intention to leverage this against the US, one AFR journalist wonders if Albanese is sending a ‘confused message on Australia’s relationship with the US’. How the journalist managed to divine Xi’s intentions is anyone’s guess.

The media’s tendency to invent binaries, set up straw men or invoke the bogeyman in order to milk any potential conflict is understandable. After all, carefully made progress or quiet and successful negotiations don’t make click-worthy headlines. But it is particularly unfortunate in foreign policy reporting, given the broader community is either ‘uninterested’ — as former AFR international editor James Curran suspects — or possibly interested, but unable to get accurate and independent information from outside the media.

At the risk of stating the obvious, framing every China-related foreign policy initiative and decision in terms of its implications for the US alliance — or vice versa — denies Australia’s capacity for independent foreign policy thinking, and forgets that both China and the US make their own decisions about Australia according to their own respective national interests.

In going to China or hoping to meet Trump, Albanese apparently hopes to advance Australia’s national interests, as informed by Australia’s own geography, economy and values. The binary logic of great power rivalry is most likely far from his mind. While reporting on either initiative is the job of our media, framing them by pitting the US against China seems to imagine Australia as a proxy actor in a US-China struggle, rather than as a sovereign middle power capable of shaping its own regional relationships.

Also, when our mainstream media characterises Australia’s improved relations with China as inherently undermining ties with the US, or when they report Australia’s difficulties with the US as a win for China — whether it be Albanese’s failure to secure a meeting with Trump or to obtain a tariff exemption — they seem to betray and further reinforce a zero-sum mentality.

This mentality is also rife in public and media discourse in the US when it comes to talking about China. Regardless, the US still maintains robust economic ties with China — especially in the trade, investment and technology sectors — despite the two nations’ strategic competition. For instance, in 2024, US-China trade was still worth over US$580 billion, and American companies like Apple and Tesla remain heavily embedded in China — although Trump’s tariff war could drive such companies to set up shop elsewhere in Asia.

Further, if the US can trade with China by exploiting Australia’s difficult relationship with China, it doesn’t seem to hesitate. This is evidenced by America and its allies reportedly benefiting from China’s economic coercion campaign against Australia a few years ago, which created challenges for Australian exporters. Some Australian exports previously destined for China were diverted to other markets, including the US.

The US may talk about its relationship with China as a zero-sum game, but this often isn’t the case in practice. So, the question for Australia is this: why should a middle power like Australia buy into this mindset?

Interestingly, in stressing the need to have our wagon permanently hitched to the US, Barnaby Joyce taught the Australian journalist a timely geography lesson: ‘You need to understand that we live in the realm of the Western Pacific.’

Indeed, Australia lives in the realm of the Western Pacific, alongside our New Zealand cousins across the Tasman, our other Pacific family members, and our Asian neighbours. Most of them are, like Australia, also living with the tension between the two big powers, but without falling into binary thinking — few are working themselves into a lather over how to serve two masters. Hedging is a common international relations strategy that our East Asian, South-East Asian, and Pacific neighbours have clearly mastered.

In reality, diplomacy — especially for a middle power in a multipolar Asia-Pacific — requires managing tensions, not choosing sides. The Albanese government is trying hard to manage the US-China tension while engaging with both powers where interests align (e.g., trade with China, security with the US). But clearly this is not good enough for our conservative media and Coalition politicians, and unfortunately, as Albanese’s China visit draws closer, we are going to see more of this.