- Posted on 21 Jul 2025

This article appeared in Asialink on July 21 2025.

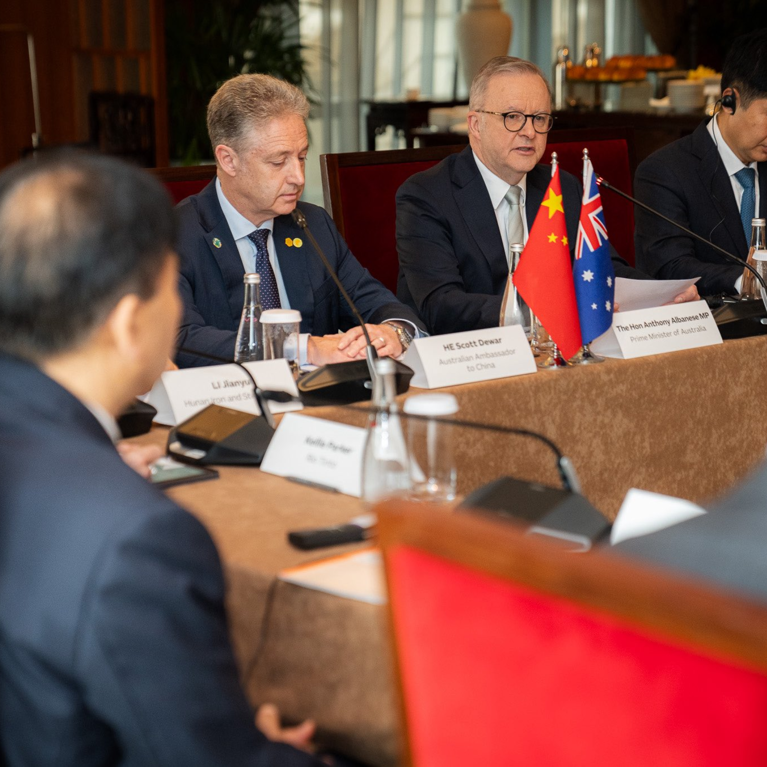

As Prime Minister Anthony Albanese concludes his second visit to China, the bilateral relationship appears to have entered a more stable, if still tightly managed, phase. Over six days across Shanghai, Beijing and Chengdu, the visit underscored Canberra’s effort to expand economic ties, while clearly defining strategic boundaries.

The tone of the visit reflected a government more certain of its footing. Backed by a strong electoral mandate, Albanese signalled a foreign policy reasserted on Australia’s own terms–-neither reactive nor deferential, and more openly grounded in national interest. Rather than positioning itself as caught between powers, Canberra is presenting itself as a sovereign actor capable of pursuing engagement without compromising on core principles.

The visit also served to emphasise that engagement efforts are not unilateral. For Beijing, stabilising ties with Canberra serves a different, but complementary, purpose. It allows China to demonstrate functional diplomacy with a US ally amid rising strategic pressure, while safeguarding access to essential commodities. Australian iron ore, lithium, copper and LNG remain critical inputs for China’s industrial and energy sectors. Even as Beijing pushes for supply chain diversification, its dependence on Australian resources has proven durable and, in key areas, not easily substitutable in the near term. That reality is particularly salient as China grapples with a slowing economy and persistent structural headwinds, lending added weight to its interest in managing tensions and keeping channels of trade predictably open.

This was evident in the leaders’ own words. In Prime Minister Albanese’s opening remarks during his July 15 meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping, the Prime Minister described a ‘positive’ relationship as being in Australia’s national interest, defining engagement as a necessity as opposed to an accommodation. Xi, for his part, spoke of a relationship that had ‘turned around’ through ‘joint efforts’ and was now delivering ‘tangible benefits’ to both countries.

This mutual framing of recovery, from the nadir of COVID-era embargoes by Beijing that blocked over $20 billion of Australian exports, suggests that the stabilisation of ties serves both governments’ broader economic and diplomatic agendas, although the structure of this recovery remains circumscribed.

Albanese prefigured this approach in a July 5 speech invoking John Curtin. The wartime prime minister’s decision to assert Australian priorities against the preferences of both Washington and London was presented by Albanese not simply as historical reflection but as precedent for the government’s current foreign policy doctrine. Curtin, Albanese argued, gave Australia ‘the confidence and determination to think and act for ourselves.’ In this framing, the message is clear: Australia is committed to its partnerships but not subordinated to them.

This principle was evident throughout the visit, not least in Albanese’s insistence that Australia’s economic engagement with China should not be conflated with US trade dynamics. In response to questions about US trade policy under Donald Trump, Albanese described Australia’s relationship with China as ‘very separate’ from that of the US, pushing back against the idea that Canberra’s position on trade should mirror Washington’s. His earlier remark that the US’ tariffs were ‘not the act of a friend’ was a pointed reminder that alignment does not mean acquiescence.

Reinforcing this emphasis on sovereign decision-making, Trade Minister Don Farrell said, ‘We don’t want to do less business with China, we want to do more business with China… We’ll make decisions about how we continue to engage with China based on our national interests and not on what the Americans may or may not want.’ Treasurer Jim Chalmers similarly described China as ‘a really crucial part of our prosperity’ and ‘an important and obvious focus of our economic diplomacy.’ The logic of engagement with China, as the government frames it, is structural. As the Prime Minister repeated throughout the course of his visit, China buys more from Australia than the next four markets combined, while exports to the US accounts for less than five percent of Australia’s total.

Still, the US alliance remains central to Australia’s defence and strategic planning, particularly through the AUKUS security partnership. But even here, the government has resisted pressure to provide assurances about how nuclear-powered submarines might be used in a regional conflict. The Treasurer has also made clear that core domestic institutions, like the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, are not bargaining chips for trade favours. As Foreign Minister Penny Wong said during a July visit to Malaysia, ‘[T]wo countries can be the strongest of allies without agreeing on every single element of policy’.

This approach of deliberate independence came under quiet scrutiny during the visit, when Albanese was pressed to respond to recent signals from US defence officials urging greater clarity on Australia’s potential role in a Taiwan conflict. Maintaining Australia’s longstanding position of strategic ambiguity and reaffirming support for the status quo, the Prime Minister refused in to be drawn into hypotheticals. It was a deliberate choice: to support regional deterrence without endorsing a forward-leaning posture or signalling alignment in advance of any conflict.

That same logic has shaped Canberra’s handling of foreign investment and critical infrastructure. Albanese used the visit to reiterate that decisions on assets like the Darwin Port, currently leased to the Chinese company Landbridge, would be made solely on national interest grounds. While Beijing has been critical of the proposed move, the matter was only referred to in veiled terms by China’s leadership, suggesting that a principled firmness, if clearly articulated, does not necessarily provoke diplomatic fallout.

The economic component of the visit reflected a pragmatic effort to deepen trade while building greater resilience into the relationship. Commodities continue to anchor bilateral trade. But Canberra is pursuing opportunities to add value within that structure and reduce exposure to future political disruption.

Steel decarbonisation featured prominently as a way of layering strategic innovation onto existing export strengths. Australian firms such as Fortescue, Rio Tinto and BHP are collaborating with Chinese steel manufacturers like Baowu and HBIS to develop lower-emissions steelmaking processes. These initiatives, aligned with both countries’ climate goals, represent a shift from raw resource dependency toward more technology-intensive forms of industrial cooperation that are both commercially viable and politically defensible.

The government remains alert to the risks of overconcentration. While trade with China in core sectors is recovering, diversification remains a priority. Australia’s broader trade agenda reinforces this intent, with Canberra expanding engagement across Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East and Europe.

What distinguishes this visit – and Albanese’s first – from earlier efforts to manage the China relationship is not simply tone, but the structure of engagement Canberra is trying to maintain. Under the Morrison government, diplomacy gave way to megaphone messaging and retaliatory trade measures. Albanese’s approach treats dialogue not as a concession, but as a method of managing risk. ‘If you don’t have communication,’ he said during the trip, ‘you can have misadventure and misinterpretation.’

The broader ambition, while understated, is significant. Albanese has presented Australia as a state capable of navigating major-power competition without becoming its proxy. His messaging throughout the visit emphasised the importance of measured, consistent diplomacy in an increasingly contested Indo-Pacific, not to dilute alliances, but to maintain strategic autonomy.

None of this eliminates the structural tensions that persist in the Australia-China relationship. Longstanding flashpoints such as the South China Sea, Taiwan and cybersecurity, among others, continue to weigh heavily. The risk of economic coercion remains a live concern, particularly given China’s track record. As competition between Beijing and Washington intensifies, the space for middle powers to manoeuvre may continue to narrow.

Yet what Albanese has advanced is a coherent foreign policy that is not derivative of alliance expectations or constrained by binaries. Sovereignty, in this framework, is not isolation nor equidistance, but selective engagement defined on Australia’s terms.

By invoking Curtin, Albanese articulated a contemporary doctrine: that Australia’s foreign policy must be principled but adaptive and rooted in a sense of self. In China, that principle was exercised. The harder test will be sustaining it.