- Posted on 20 Nov 2025

- 4 minutes read

Research tracing the unexpected spread of subtropical coral species in the temperate waters around Sydney is celebrated with a NSW Premier's Prize for Science and Engineering.

When scientists discovered coral species Pocillopora aliciae was migrating into the prime real estate of Sydney Harbour, it triggered new research into this complex ecosystem under the waves.

The Sydney Coral Project is delivering the first comprehensive mapping and assessment of Sydney’s corals, an understudied yet rapidly changing part of the state’s marine ecosystems.

It is an ambitious collaboration between UTS, the Sydney Institute of Marine Science, the University of Sydney, the Indigenous Gamay Rangers and a network of citizen scientists.

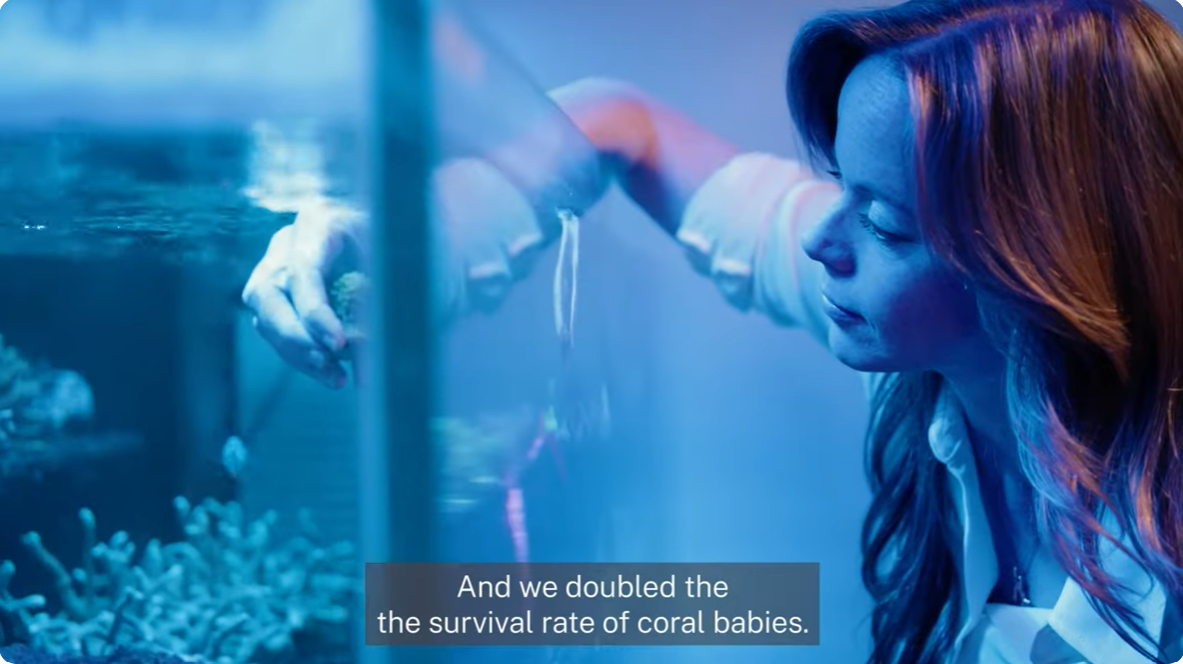

The project’s lead researcher, Dr Jen Matthews, has been awarded a NSW Premier’s Prize for Science and Engineering as Early Career Researcher of the Year (Biological Sciences).

“The collaborative team in the Sydney Coral Project, including volunteer citizen scientists and the Indigenous Gamay Rangers, are working to understand what’s happening now and what may happen in the future,” she said.

“Climate change is altering the waters around Sydney and we’re watching in real-time as our marine ecosystems adapt and change.”

Dr Jen Matthews

Deputy Team Leader, Future Reef Program

Dr Matthews is an award-winning marine biochemist and ecologist who is building better understanding of coral health and nutrition.

She is Deputy Team Leader of the Future Reefs Program in the UTS Climate Change Cluster and a UTS Chancellor’s Research Fellow,

Her work explores the interactions between coral hosts and their microbial hosts including how feeding coral larvae “baby food” can build more resilient reefs.

She has previously been awarded the NSW Tall Poppy Science Award, a Royal Society of NSW Early Career Research and Service award, a Superstar of STEM and was recently named a finalist in NSW Australian of the Year.

As part of the Sydney Coral Project, Dr Matthews has been examining the relationship between the two species found in Sydney Harbour – the temperate Plesiastrea versipora and subtropical Pocillopora aliciae species – and how warming waters might change the balance between the two and what this means for local biodiversity.

It combines cutting-edge science with community engagement to understand how corals are adapting to Sydney’s waters and what it means for our marine future.

“While it is a great honour to receive this award, it really reflects the talent and dedication of the entire team,” Dr Matthews says.

“This project shows what’s possible when scientific expertise, Indigenous knowledge and community passion come together.”