- Posted on 25 Sep 2025

- 4 mins read

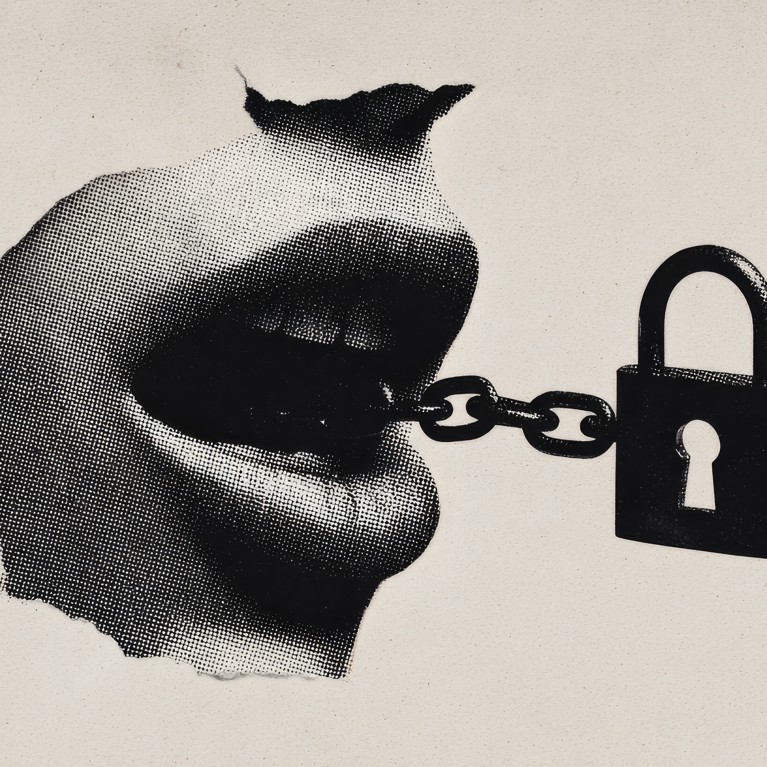

Despite being elected partly on a platform of increased government transparency, the Albanese government is by many accounts even less transparent than its predecessor. Research released by the Centre for Public Integrity in July showed that the current government is performing worse on both Freedom of Information requests and Senate production orders than the Morrison administration. These are critical means for informing the public about government decision-making. But the government’s poor performance is evidence not so much of operational difficulties as of a deeper problem in how it understands its relationship with the media and with the public. On this view, information about the workings of government is a privilege to be granted, rather than a duty to be fulfilled.

This understanding is revealed across a spectrum of examples. At one end, we might hold up the government’s refusal to drop the prosecution of whistleblower Richard Boyle; at the other, perhaps, the disrespect shown to local journalists who were excluded this month from the prime minister’s press conference during the Pacific Islands Forum. While they were not Australian journalists, they have as much, if not more, of an interest in the Albanese government’s plans in the Pacific as Australians do. And part of this interest is in understanding how Australia projects its relationship with Pacific nations. While Albanese spoke of Australia’s membership in the ‘Pacific Family’, his exclusion of local journalists, as Jone Salusalu put it in the Fiji Times, ‘threatens to reinforce a narrative that Australia is more focused on controlling its own story than on being a responsible regional partner to Pacific communities.’

That narrative is being reinforced on our own shores, too, in reports of a creeping parliamentary culture of 'strings-attached drops', where press releases are embargoed until a particular time of the government’s choosing and many include instructions that no third-party comment is to be included in the initial coverage. ABC reporter Gareth Hutchens describes being subjected to a tirade of abuse by a Turnbull staffer — an ex-journalist no less — for including a third-party quote in his write-up of a release, even though it was taken from previous coverage of the issue.

The government should have no expectation that journalists will support their own carefully managed narrative. The public’s ‘right to know’ is not satisfied by the amplification of government narratives across the media, but only by the application of the rigorous scrutiny appropriate to a free and robust democracy. Hutchens argues that it is within the media’s power to curtail the culture of parliamentary capture. But to do so, they will have to overcome the problem of collective action, where no journalist wants to break ranks for fear of being ostracised by the government. Here, perhaps, industry bodies could play a role, including the seemingly moribund Right to Know coalition. This collective action could go beyond a refusal to kowtow to the government’s demand to control the narrative. There is certainly room to consider developing a code of conduct that sets explicit expectations for government practice. While it may not be enforceable, it would at least provide a public benchmark.

Looming over all this is the prospect of the government legislating its warped understanding of the public’s right to know in proposed reforms to the Freedom of Information Act. These would allow all but the simplest requests to be denied on the basis of the work it takes to comply with them and expand the range of documents exempt under cabinet privilege. Now would seem an opportune time for the industry to band together once again.