Often hidden and complex, domestic violence affects far more lives than most people realise. Through UTS’s Domestic and Family Violence Research Network, nearly 50 experts are turning research into practical solutions that support women and children while driving meaningful change.

Once understood mainly as physical harm, domestic violence is now recognised in many forms including coercive control, verbal, financial and cultural abuse. Technology has added new risks. In the past, physical distance could offer some sense of safety, but now social media, tracking apps and digital monitoring can follow victims everywhere, making it harder to find relief.

Addressing domestic violence requires action from every angle. The Domestic and Family Violence Research Network works across support services, workplace policy, financial abuse, technology-facilitated abuse, legal reform, education, economic impact, anti-slavery and elder abuse.

Within the network, three researchers from business, design and law show how their work is shaping policy, creating safer spaces and informing long-term reform.

Together, their research turns evidence into action.

A movement takes shape

Few understand how far women’s advocacy has come better than researcher, journalist and activist Dr Anne Summers AO. When she arrived in Sydney from Adelaide in the early 1970s, she was already active in Women’s Liberation and hoped to continue that work in her new city.

Settling into an inner-west share-house with another feminist, both completing their PhDs, Summers soon witnessed domestic violence up close, an experience that stayed with her.

“One night we heard a knock on our back door,” she recalls.

“When we opened it, there was a young girl with a baby. She’d climbed a six- or seven-foot fence from the adjoining house, carrying her baby – that was how terrified she was to get away from her husband.”

At the time, the women’s movement was gaining momentum, but domestic violence was not yet part of the national conversation.

“We were thinking about equal pay, abortion rights, childcare,” Summers says.

“We hadn’t really considered violence.”

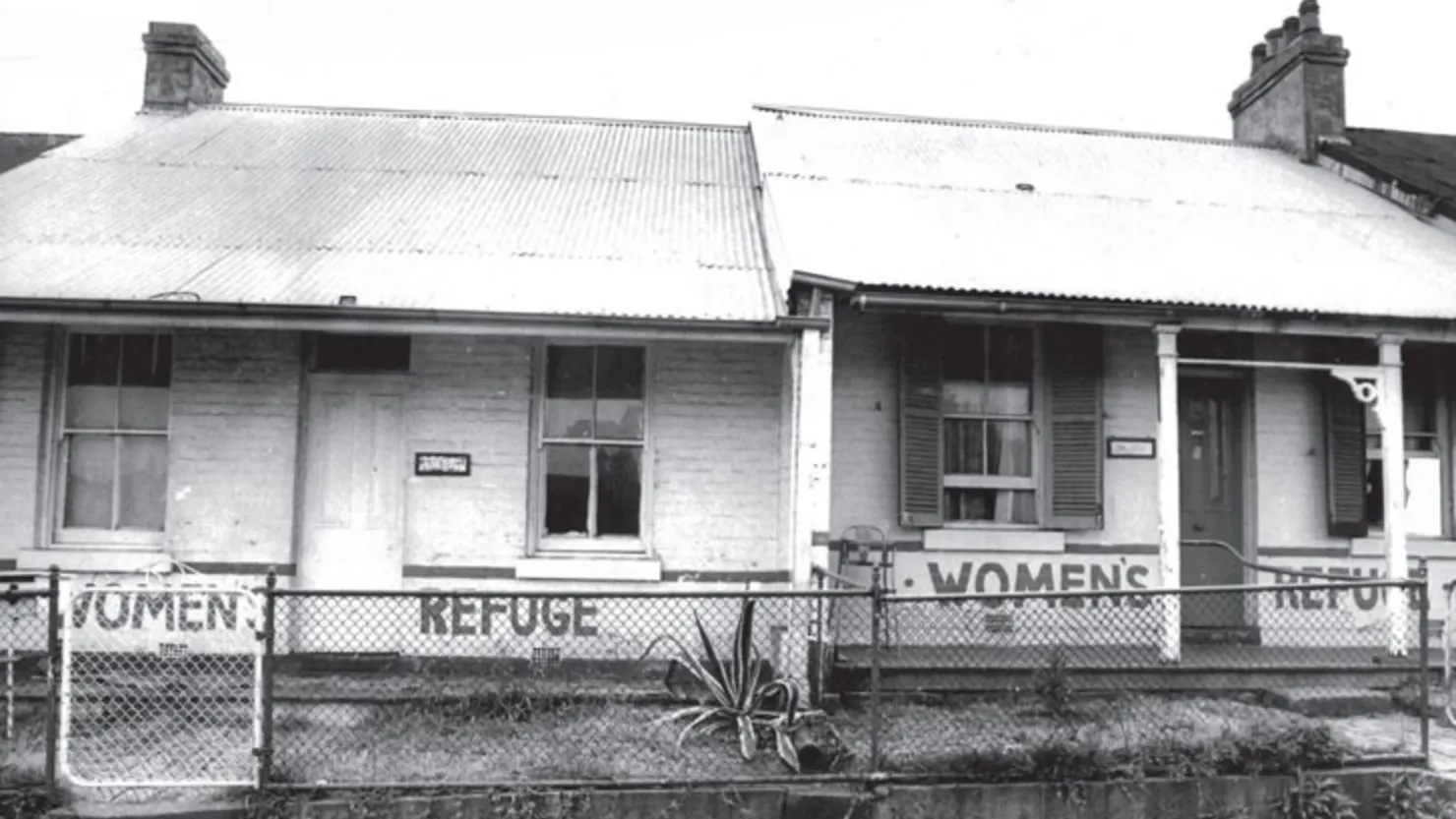

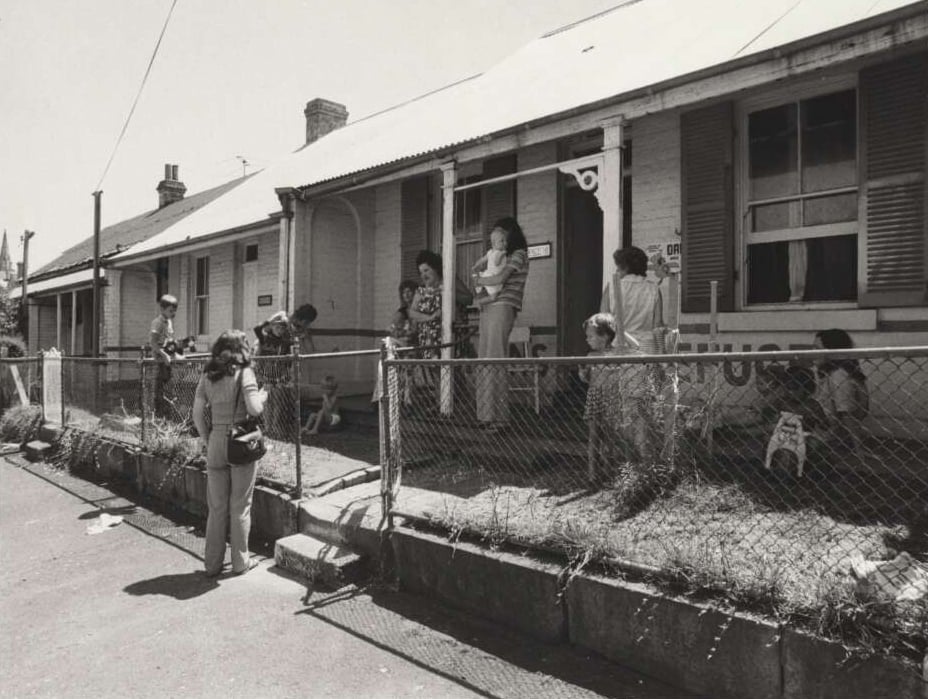

Determined to change that, Summers drew inspiration from Chiswick Women’s Aid in London. Working with five other women, she began searching for a house to establish Sydney’s first women's refuge. They eventually found a vacant property in Glebe.

Momentum grew quickly. At a two-day “teach-in” at the Teachers Federation Hall in March 1974, woman after woman stood up to share her experiences of abuse or mistreatment.

“There were just so many stories,” Summer recalls.

It was at this event that Summers and her colleagues announced their plans for a refuge. Days later, planning became action.

“A week after the teach-in, we broke into the house, changed the locks and declared squatters’ rights,” she says.

“We refused to pay rent to the owner, the Church of England, which had left the house vacant intending to sell it to the federal government for low-income housing.”

The house had a name: Elsie. It became Elsie Women’s Refuge, Australia’s first shelter for women and children escaping violence, and a defining moment that changed the national conversation.

Returning to research

With Elsie established and running, Summers turned her focus back to writing.

“I was doing a PhD, but what I was really doing was writing my book Damned Whores and God's Police,” she says.

“I wanted to tell Australian women about the specific Australian ways in which we were oppressed.”

The book, published in 1975, launched her writing career and soon led her into journalism, where she spent almost a decade at The National Times and The Australian Financial Review in Canberra.

She later moved into public service as head of the Office of the Status of Women in 1983, the year the Sex Discrimination Act was being passed. Domestic violence still wasn’t a central policy issue, but that began to shift by 1992, when Summers served as women’s adviser to Prime Minister Paul Keating and violence had become a major concern for women voters.

After her time in politics, Summers returned to journalism. It wasn’t until many years later, during a chance conversation with a board member of the Paul Ramsay Foundation, that domestic violence research became the prime focus of her work. The Foundation awarded her its inaugural fellowship, providing $250,000 to undertake a major project hosted by UTS.

That work became The Choice, a landmark, data-driven study examining how women are forced to choose between safety and financial survival, often ending up in what was termed “policy-induced poverty.”

Using customised data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Summers and her small team examined the experiences of women who became single mothers after leaving violent relationships. She found that in 2016, nearly 60% of single mothers with children under 18 had experienced partner violence, compared with 21.9% of other women. Only half were employed; the rest lived in poverty because government benefits did not cover basic living costs.

The per-fortnight increase to the Single Parent Payment introduced after Summers’ research.

This was policy-induced poverty. Women were making the choice between leaving violence and surviving financially.

Summers’ research goes beyond numbers. It tells the story of women navigating impossible choices and the systemic barriers that shape their lives, bringing to light experiences often overlooked in policy discussions.

Her report captured the attention of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, who was himself raised by a single mother. In response to these findings, the government restored support that had previously been cut, extending the single-parent payment until a child turns 14 and increasing it by $176.90 per fortnight.

This change demonstrated how research and advocacy can work together to create real outcomes. In 2023, the Paul Ramsay Foundation awarded Summers $2 million to continue her research on two more projects: The Cost and a longitudinal study tracking intimate partner violence.

The ripple effect of evidence

Summers’ second project, The Cost, explored the economic impact of domestic violence and showed how abuse can limit women’s ability to be financially independent. Women who had experienced partner violence were less likely to be in paid work, with participation at 76.1% compared to 81.4% for women who hadn’t. For those subjected to economic abuse, the gap widened to 9.4%.

“These numbers aren't just statistics,” explains Summers.

“They show how domestic violence erodes women's independence, safety and ability to work and support their families.”

The research also highlighted deep inequities in education. Using data from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health, Summers’ team tracked women born between 1989 and 1995 through their university years. Over four years, 9.7% dropped out due to domestic violence. The long-term effects are profound: women without a degree earn around 41% less over a lifetime.

“Women are being penalised for something that happened to them when they were 21,” she says.

Building on this body of work, Summers and her team are now designing a national longitudinal study to track intimate partner violence and give the federal government the tools needed to prevent, respond to, and ultimately end domestic violence.

She remains clear-eyed about the challenge ahead.

There’s been more recognition, more services, more awareness, but the urgency has faded. One woman a week is still killed. We know what works, yet it’s not happening fast enough.

Trauma-informed design

While Summers’ research explores the social and policy barriers women face, Dr Samantha Donnelly, a lecturer in Interior Architecture, focuses on the spaces where women seek safety, and how design can foster calm, dignity and care.

Donnelly didn’t set out to become an expert in refuge design. Her work in women's shelters began when she was asked to help a refuge manager replan communal kitchens and design kitchenettes and ensuites.

“It was a revelation,” she recalls. “Working with a fierce team of women who had really limited funding and for a cause that made women and families safer. I felt like I’d finally found my place.”

That project led her to a realisation: there was almost no research on women’s refuges as buildings. This gap became the focus of her PhD on trauma-informed design, examining how architecture can support residents and, as she later discovered, the wellbeing of the staff who care for them.

Number of women in Australia staying in a refuge or shelter the first night after their final separation from a violent partner in 2016.

Creating spaces that support residents and staff

Through her research, Donnelly found that refuges were carefully designed by refuge staff to meet residents’ needs. With minimal budgets, they created private rooms, garden nooks and multiple communal areas which gave women choice and a sense of control.

“In shared refuges, residents really valued the freedom to choose where they spent their time,” she says.

But her PhD revealed something less visible. It was the staff that often had little or no private space. Their offices were often cramped, cluttered and shared between multiple workers, leaving no space for focused work or sensitive conversations.

“Some workers would sit in their car just to have a bit of quiet time,” she recalls.

“The work they do is also intense. Staff juggle reporting, court appearances, emotional support and being available around the clock. As demand rises and teams grow, they constantly need to reconfigure shared spaces just to make them fit.”

For Donnelly, trauma-informed design must consider both residents and staff. This means well-planned, flexible and restorative workspaces that improve staff wellbeing, which in turn supports better care for residents.

“Even the residents noticed,” she says. “‘When they’re happy, we’re all happy,’ they said. “We must ensure the house works well for the workers.”

From evidence to action

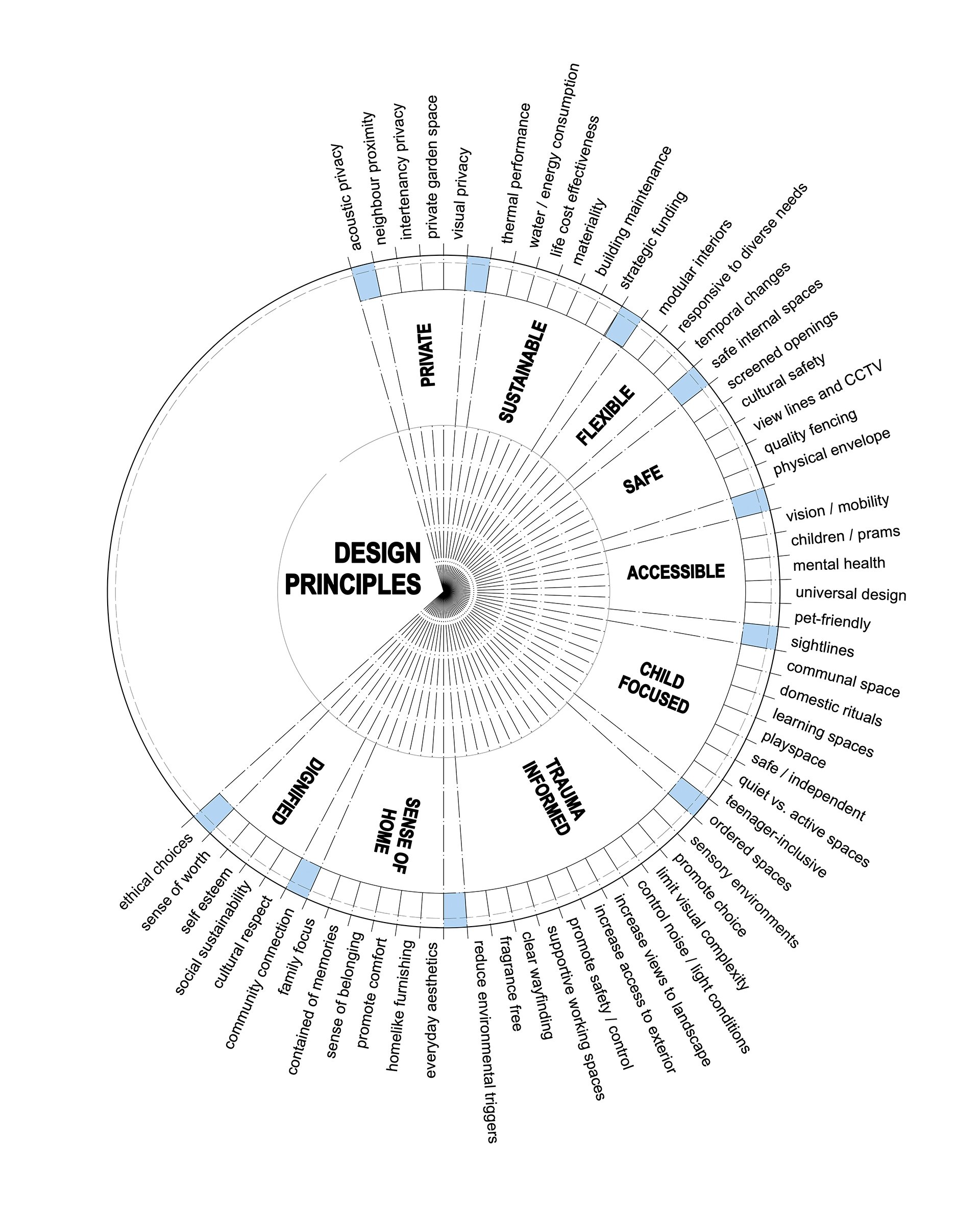

Donnelly didn’t intend her PhD findings to stay on paper. As part of her research, she developed a nine-principle Design Guide for Refuge Accommodation, along with practical fact sheets to help service providers apply trauma-informed principles in real spaces.

She worked closely with developers and government agencies during NSW’s 75-new-refuge initiative, making sure evidence shaped design from the very beginning.

Today, her resources are used by NSW government agencies and community housing providers to create spaces that feel safe and dignified. They emphasise flexibility, child-friendly design and a sense of home. Private and communal areas give residents choice and support wellbeing, while adaptable, calm, well-organised workspaces help staff manage the demands of their role.

Donnelly also brings this work into the classroom, taking students into live shelters so they can see trauma-informed design in practice.

“The students are re-energising to work with. They’re committed to making a change through their skills as designers,” she reflects.

Redesigning the law to protect women

While trauma-informed design can create more supportive spaces for women, lasting change also means addressing the legal systems that govern their safety. That’s where Associate Professor Jane Wangmann comes in. A researcher in the Faculty of Law, she focuses on how legal frameworks can recognise and respond to the lived realities of domestic and family violence.

After finishing law school in the early 1990s, Wangmann took her first job with the Australian Law Reform Commission, working on its inquiry into women’s equality.

"Violence kept coming up in the public hearings," she recalls.

"We were looking at equality, but it became clear that violence touches every part of it."

That realisation shifted her work. From community legal centres to government policy and now UTS, Wangmann has spent decades working on a larger question: how do you build legal systems that truly respond to domestic and family violence – in all its forms?

A turning point: understanding coercive control

One answer lies in understanding coercive control – a term that's only recently entered public debate but has long been central to how advocates describe abuse.

"Coercive control isn't new," Wangmann explains. "Since the 1970s, we've used terms like power and control or social entrapment. It's about patterns of behaviour, physical and non-physical, that erode a victim's liberty and freedom."

Unlike physical assault, coercive control unfolds over time, often in ways that are subtle and often hard for traditional legal systems to identify or act upon.

"Victims often describe feeling trapped, like walking on eggshells or trapped in a web. They never know what will happen and perpetrators can be very creative in targeting behaviours to the person they know best."

The push to criminalise coercive control gained momentum following high-profile homicides and findings from NSW's Domestic Violence Death Review Team, on which Wangmann serves. The team found that nearly all intimate partner homicides were preceded by coercive and controlling behaviour.

One such example, referenced in Summers’ The Choice report, is the tragic case of Hannah Clarke and her three children. After her death, Hannah’s parents and brother described in a television interview how her husband controlled every part of her and the children’s lives. He dictated what she could wear and whether she could go out, punished the children if she refused his demands for sex, and prevented her from using contraceptives.

Progress and limits

Cases like Hannah's helped push legal reform. In July 2024, New South Wales introduced a standalone offence, the first of its kind in the state, with Queensland and South Australia following soon after.

Wangmann welcomes the change but remains cautious.

“In the first year, police recorded around 300 coercive control matters, compared to nearly 40,000 domestic violence assaults,” she notes.

“It’s narrowly drafted, difficult to prove and requires demonstrating intent and patterns over time. But it’s definitely a start.”

Criminalisation, she stresses, is only one part of the picture.

“Very few survivors report to police. Many seek help through family law and protection orders, which have recognised patterns of coercive control since 2012, yet these systems rarely get the same attention.”

Her research also looks beyond legislation, examining how police, lawyers and judges can better understand coercive control in everyday practice. She has evaluated court support programs too, highlighting how legal processes can compound trauma.

“Cross-examination can be brutal. Even with support, the process can retraumatise. Many victims say they wouldn’t go through it again.”

Despite these challenges, Wangmann sees progress in naming and recognising coercive control.

Law isn’t leading; it’s catching up. Women have always talked about financial abuse, verbal abuse, denigration. Now we have the language and a law to recognise it.

Domestic Violence Research Network

As co-director of the UTS Domestic Violence Research Network, Wangmann knows change doesn’t happen in silos.

"Domestic and family violence isn’t just a legal problem; it’s a social, health, economic and cultural issue," she says.

"To make lasting change, we need to connect those perspectives. That’s what the Network is about, bringing researchers, frontline workers and advocates together to share ideas and push for solutions."

It’s early days, but the ambition is clear: link diverse research and practice with lived experience, influence policy and rethink the systems and spaces that shape women’s lives.

"You cannot do good work without strong relationships with the sector," Wangmann reflects.

"If I’m researching criminal law, I need to talk to people with lived experience, advocates and other professionals. We all need to work together."

Because safety isn’t just the absence of violence; it relies on laws that protect, support that empowers and action from all of us.