Last week, the presiding coroner in the 2019 Christchurch terrorist attack ordered an inquiry to examine if the Australian terrorist, who killed 51 people and live-streamed the attack, was radicalised online. The coroner, Brigitte Windley, will focus on the gunman’s online activities between 2014 and 2017 – a window that had not been covered by earlier investigations, including the Christchurch Royal Commission report, which was released after 20 months of consultation.

The report’s lack of attention to his online activities had come as a surprise to digital media researchers, including myself. After all, the preliminary investigations found that the gunman had spent time on YouTube and the message boards 4chan and 8chan. His strategic use of a social media platform to live stream the attack to a global audience was clearly indicative of his disconcerting relationship with digital media platforms. That said, the 800-page RC report has paved the way for future investigations, such as that ordered by Windley last Thursday. Now if, through this new inquiry, it is established that social media had a significant role in the gunman’s radicalisation over the years, it will be a win for those who have been arguing for more accountability of and responsibility by social media companies and other digital media platforms. For now, the coroner and the investigation team have been facing some ‘monumental hurdles’, mainly because the terrorist had made attempts to wipe parts of his digital footprint before committing the attack on the two mosques.

No inquiry can bring back what the bereaved families have lost. However, this new investigation may be able to offer insights into whether and/or how these deaths could have been prevented if the digital platforms he was using were able to catch and flag suspicious online behaviour and activities, such as in this case, the purchase of arms by a foreign citizen, uploading the manifesto before the attack, and sharing and promoting far-right extremist ideologies.

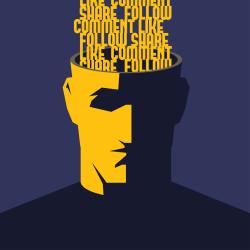

Sadly, religious radicalisation is not the only worry of Australian security agencies. Earlier this year, we heard ASIO boss, Mike Burgess, warning of more ‘angry and alienated Australians’ – some as young as 13 years old – who were prone to violence after being exposed to online echo chambers of extremist ideology, mis- and dis-information, and most importantly, conspiracy theories communicated across closed groups and spread online. The pandemic lockdowns may have made it worse, increasing the serious risk of lone attackers idealising executions, taking up arms, and martyrdom.

Vulnerable individuals, including younger people, are of course more likely to get inspired by extreme rhetoric that is both overtly and implicitly promoted by social media and influencers on various digital platforms. This can amplify radicalisation that can become a pathway to both ideologically and religiously motivated violence in real life. While we, as researchers, are trying to identify these links, for now, the coroner’s inquiry is a promising step towards exploring how users are radicalised online and why digital platforms need to be more accountable.

To complement the piece is my talk with Dr. Teagan Westendorf, who is an analyst at Australian Strategic Policy Institute. Teagan researches power politics; the law, ethics and national security implications of digital technologies; and radicalisation and violent extremism.

Watch it here:

Ayesha Jehangir, CMT Postdoctoral Fellow

This article was first published in the CMT newsletter of 13 May 2022, which dealt with key issues of public interest - Election misinformation, radicalisation through social media and public interest journalism and more. Click to read the full edition here. If you want to receive this newsletter direct to your inbox, please subscribe here.