The dismissal of Ben Roberts-Smith’s defamation suits against several Australian news outlets has understandably brought a sense of vindication to much of the Australian media, as well as speculation on what will come next. Justice Anthony Besanko upheld the defendants’ claims that the defamatory imputations in their investigative reporting were, in the majority, substantially true. These included that Roberts-Smith murdered and ordered the murder of prisoners, thus committing war crimes.

This raises a question about how the media should describe the verdict, and indeed, Roberts-Smith himself. There appears to be a consensus that the verdict means it is legitimate to call him a murderer and a war criminal. In one sense, this seems right: the judge found the imputations to be substantially true, and the media can thereby republish those claims without fear of further defamation.

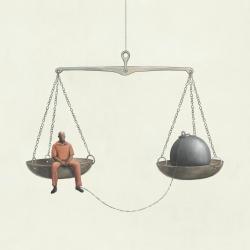

As much of the reporting has also observed, there is a difference between what will pass muster in a civil case – namely, the balance of probabilities – and the lack of reasonable doubt that is required to prove criminal charges. The difference is brought to the fore when we consider what might happen if criminal charges are laid against Roberts-Smith, and he is acquitted. Could we then continue to legitimately call him a murderer and a war criminal? It seems not, yet the civil verdict would remain unaffected by the outcome of the criminal trial.

There is a subtle difference between coverage of the verdict and the original reports that were the subject of the trial. The latter generally used the language of allegation, while the language of recent reporting, particularly in headlines, has been less qualified, even categorical. This seems a mistake, even if only because it precludes the nuance that may be needed later. Just as Justice Besanko qualified his own findings with a lengthy discussion of the civil standard of proof and the procedures for weighing evidence, it would seem judicious for journalists to qualify their claims. This might mean more than just referring to the civil standard in reporting the judge’s verdict, but instead conveying a sense of probability or likelihood appropriate to findings established on that standard. Consider what ‘the balance of probabilities’ means, and proceed on that basis.

Michael Davis, CMT Research Fellow

This article is from our fortnightly newsletter published on 16 June 2023.

To read the newsletter in full, click here. Subscribe here.