That’s happening in Australia with the help of research out of the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) focused on technology-enhanced learning.

Research led by Dr Jane Hunter of the Centre for STEM Education Futures has been looking at two areas in particular in recent years: the use of technology for teaching and learning, and helping teachers integrate STEM into learning from Kindergarten onwards that goes beyond science and maths curricula.

This research has increased and improved the use of digital technologies in school education in Australia and overseas, directly enhancing students’ creative and critical thinking skills and engagement with learning. In turn, the work has earned acknowledgment for its ‘high impact’ in the inaugural Engagement and Impact Assessment carried out by the Australian Research Council on behalf of the Federal Government.

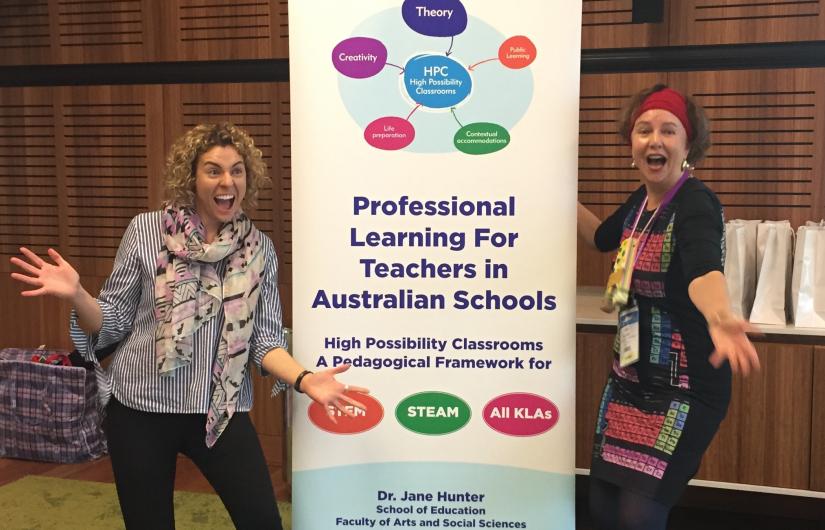

Thousands of teachers have now been exposed to the High Possibility Classrooms (HPC) framework.

HPC is a framework for pedagogy that “supports teachers to think through their planning, the subject matter they teach, and the ways learning can be reimagined through innovative uses of technology to engage and motivate students,” Dr Hunter says.

“It encourages students to inquire and adopt critical thinking, and it builds the confidence and capabilities of teachers in using and experimenting with all kinds of strategies and learning processes in the classroom.”

The model emerged from insights gained from in-depth studies of technology integration in exemplary teachers’ classrooms. The framework has five conceptions and 22 underpinning themes covering teaching strategies and student learning processes.

Initially developed by primary and high school teachers in four schools, the HPC framework has in the past four years been taken up in the strategic plans at multiple schools. It’s in teacher professional development programs across Australia, in teacher education courses and has influenced both government policy and the thinking of education technology businesses.

In HPC classrooms, students use inquiry-based learning with real-world problems and work in teams to come up with solutions, knowing their results will be shared with an outside audience – via an ‘expo’ at school, an assembly presentation or on Google Classroom, say.

It changes the student’s sense of agency and what happens when they apply their knowledge.

— Dr Jane Hunter, UTS

In one project, students were asked to examine the degradation of a local waterway, which involved conducting their own research, going on site visits, using water testing kits and producing a solution to share.

This sort of project “changes the student’s sense of agency and what happens when they apply their knowledge and develop their problem-solving skills”, says Dr Hunter, a former classroom teacher and head teacher herself.

Aware of Dr Hunter’s most recent work, principals from a group of six New South Wales public schools invited her to be their academic partner for 18 months.

In this partnership, Dr Hunter worked with 22 middle leader teachers, and these teachers were partnered with less confident colleagues to support them to develop their skills in integrating STEM into teaching and learning.

Wilkins Public School in Marrickville, in Sydney’s inner west, was one of the schools. Principal Sheila Bollard, who instigated the academic partnership with Dr Hunter, says that whether teaching science, art, language or developing soft skills in students, “HPC puts the student at the centre of learning, with problem solving as the vehicle to drive the learning and technology as the tool”.

“This wasn’t about just using Google to research – it really changed what could happen in terms of students demonstrating their knowledge,” Ms Bollard says.

In one STEM project, students at the school used technology to motorise a construction made out of recycled materials. In a design challenge on natural disasters, one of the students built a ‘dustinator’ to show how dust could be cleared from a disaster site.

What impressed Ms Bollard in this mission was when she observed students failing and failing again in their attempts to find solutions but continuing to persevere because they were so engaged.

I saw one particular child who was always disengaged in this class and was amazed at his focus and concentration.

The project was personalised and meaningful, with so many layers to it.

— Sheila Bollard, Principal

During an art lesson at Wilkins students were introduced to the use of metal electric strips applied to paper, she recalls. The task was to pick their favourite quote, song or book, paint an artwork, and then illuminate it using the electric circuit. “I saw one particular child who was always disengaged in this class and was amazed at his focus and concentration,” she says. “The project was personalised and meaningful, with so many layers to it.”

Building teacher capacity and confidence in STEM subjects is supported through a pedagogical framework like HPC because it involves understanding and applying new technology to parts of the curriculum that, in the past, often involved students watching what the teacher was doing. Now students are at the centre and the learning is hands-on and minds on.

Using this approach, teachers “go on a learning adventure with the children”, Ms Bollard says.

Teachers are seeing results. Year 6 students who have been exposed to HPC are hitting high school with better STEM skills, Ms Bollard says, and the school now has seven teachers who are confidently applying the HPC framework to plan and program all their units of work.

“This academic partnership, underpinned by research, with elbow-to-elbow support at the school site involving teachers, is what I love doing most,” says Dr Hunter. “It involves trust, deep listening and respecting the important work that teachers do every day in our schools.”

Find out more

- a new book about this recent school research partnership, High Possibility STEM Classrooms: Integrated STEM learning in research and practice, is available for pre-order through Routledge.

- follow Dr Hunter on Twitter: @janehunter01

- visit the blog: highpossibilityclassrooms.com

Research team

-

Senior Lecturer, Professional Learning

Faculty/unit

-

Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

-

Centre for STEM Education Futures

Funded by

- NSW Department of Education