Throughout history, artists have imagined and created proxy universes, writes Cherine Fahd, Associate Professor of Visual Communication in the UTS School of Design.

NASA/STScI, CC BY-SA

How the James Webb deep field images reminded me the divide between science and art is artificial

The first task I give photography students is to create a starscape.

To do this, I ask them to sweep the floor beneath them, collect the dust and dirt in a paper bag and then sprinkle it onto a sheet of 8x10 inch photo paper. Then, using the photographic enlarger, expose the detritus-covered paper to light. After removing the dust and dirt, the paper is submerged in a bath of chemical developer.

In less than two minutes, an image slowly emerges of a universe teeming with galaxies.

I love it when the darkroom fills with the sound of their astonishment the moment they realise the dust beneath their feet is transformed into a scene of scientific wonder.

I was reminded of this analogue exercise when NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope shared the first deep field images. The public expression of wonder is not unlike that of my students in the darkroom.

But unlike our makeshift starscapes, the Deep Field images capture an actual galaxy cluster, “the deepest, the sharpest infrared view of the universe to date.”

This imaging precision will help scientists to solve the mysteries in our solar system and our place in it.

But they will also inspire continued experiments by artists who address the subject of space, the universe and our fragile place in it.

Creating art of space

Images of the cosmos afford considerable visual pleasure. I listen to scientists passionately describing the information stored in their saturated colours and amorphous shapes, what the luminosity and shadows are, and what lurks in the deep blacks that are spotted and speckled.

The mysteries of the universe are the stuff of science and of the imagination.

Throughout history, artists have imagined and created proxy universes: constructions that are lyrical and speculative, alternate worlds that are stand-ins for what we imagine, hope and fear is “out there”.

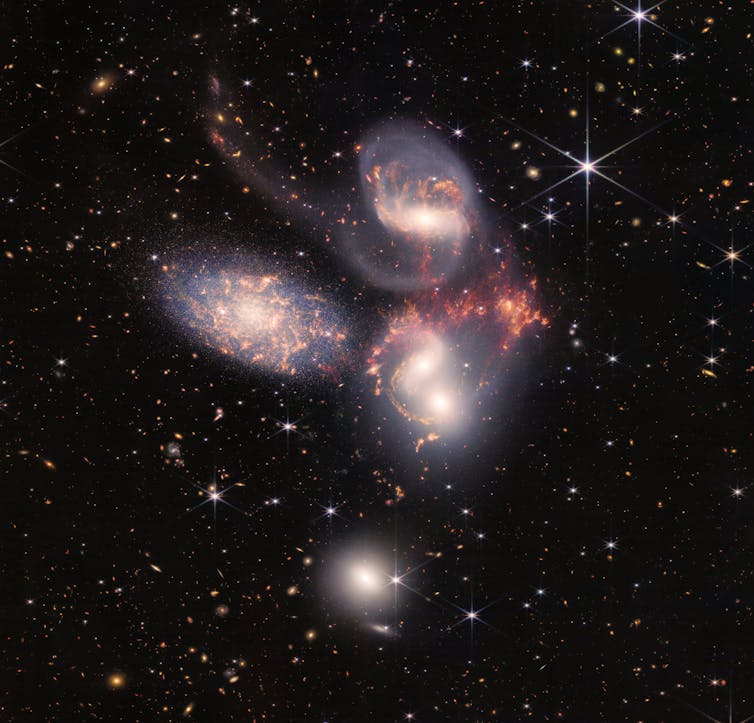

The James Webb Space Telescope’s image of Stephan’s Quintet. NASA/STScI, CC BY-SA

There are the photo-real drawings and paintings of Vija Celmins. The night sky painstakingly drawn or painted by hand with extraordinary detail and precision.

There is David Stephenson’s time lapse photographs that read as lyrical celestial drawings reminding us that we are on a moving planet. Yosuke Takeda’s ambiguous star bursts of colour and light. Thomas Ruff’s sensuous star photos made through the close cropping of the details of existing science images he bought after failing to be able to capture the cosmos with his own camera.

There’s also the incredible work of the Blue Mountains based duo Haines & Hinterding where polka dots become stars, black pigment is the night sky, bleeding coloured ink is a gas formation. They make rocks hum and harness the sun’s rays so we can hear and smell its energy.

These artworks highlight the creative drive to draw on science for the purposes of art. The divide between science and art is an artificial one.

Pictures of our imaginations

The Webb telescope shows science’s capacity to bring us images that are aesthetically imaginative, expressive and technically accomplished but – strangely – they don’t make me feel anything.

Science tells me these shapes are galaxies and stars billions of years away, but it isn’t sinking in. Instead, I see a fabulously constructed landscape like James Nasmyth’s famous moon images from 1874.

In my imagination, I picture the Webb images as made of fairy lights, coloured gels, mirrors, black cloth, filters and photoshop.

A planetary nebula, seen by the Webb telescope. NASA/STScI, CC BY-SA

Art’s stand-ins invade my psyche. When I look at the deep field and planetary nebula, I remember that even these “objective” machine made images are constructed. The rays of light, holes and gases are artistic experiments in photographic abstraction, examining what lies beyond vision.

Imaging technology always transforms what is “out there”, and how we see it is determined by what is “in here”: our own subjectivity; what we bring of ourselves and our lives to the reading of the image.

The telescope is a photographer crawling through the cosmos, making more of the unseen seen. Giving artists more references for appropriation, imagination and also critique.

While scientists see structure and detail, artists see aesthetic and performative possibilities for asking pressing questions that concern the politics of space and place.

Art in space

Webb’s images present a renewed opportunity to reflect on the work of American artist Trevor Paglen, who sent the world’s first artwork into space.

Paglen’s work examines the political geography that is space and the ways in which governments aided by science use space for mass surveillance and data collection.

The deepest and sharpest infrared image of the early universe ever taken. NASA/STScI, CC BY-SA

He created a 30 metre diamond-shaped balloon called the Orbital Reflector, supposed to open up into an enormous reflective balloon and be seen from Earth as a bright star. It was rocketed into space on a satellite, but the engineers could not complete the sculpture’s deployment due the unexpected government shutdown.

Paglen’s artwork was criticised by scientists.

Unlike astronomers, he wasn’t trying to unlock the mystery of the universe or our place in it. He was asking: is space a place for art? Who owns space, and who is space for?

Space is readily available to government, military, commercial and scientific interests. For the time being, Earth remains the place for art.![]()

Cherine Fahd, Associate Professor of Visual Communication in the School of Design, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.