On Wednesday 5 March 2025, Dr Michele Bruniges AM delivered a keynote address at the Sydney Morning Herald's School Summit – an annual gathering of some of Australia’s foremost educators, thought leaders, and policymakers.

The speech largely focused on the research she undertook during her time as Industry Professor – Concentrations of Disadvantage at the UTS Centre for Social Justice & Inclusion, which looked at the systems, drivers, and cycles of educational disadvantage in Australian schools – and how to mitigate them. The position was supported by the Paul Ramsay Foundation (PRF) and its Fellowship program.

You can read the full speech below.

Good morning distinguished guests and colleagues. Thank you for the invitation to join you at the Schools Summit.

Could I begin today by acknowledging the Traditional Custodians of the land we meet on today. I pay my respects to elders past and present and any Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people joining us here today.

To this day, I still consider teaching my profession and reflect on how as a young kid growing up in a small country town in the Snowy Mountains in NSW, attending the local public schools played a significant role in shaping my values, strengthening my resilience, and helping me to understand how connection and a strong sense of community matters.

I learnt the value of diversity and how it provided strength and offered different insights in crafting solutions when the chips were down, and it provided a collective benefit to the teams forging new ways of doing things as the engineering feats of the Snowy Mountains Authority unfolded before the eyes of our community.

This is the environment that shaped my knowledge and helped me develop attributes which I have carried with me through my career as a teacher and public servant. I am proud of my profession and grateful for the opportunities I have had to develop a strong passion, dedication and long-standing commitment to education.

This morning, I will share with you some of the work I have done during the last 18 months with the generous support of the Paul Ramsay Foundation and the University of Technology Sydney.

I have worked with a national network of dedicated colleagues from all states and territories and all sectors in a collaborative way throughout the study and my thanks goes to each of them.

This morning, I will talk about our shared commitment to education, the challenges we face, and the opportunities we have to work together to deliver on the promise of a great education for all.

Our commitment

Australia has a strong and proud tradition of a fair go for all. The promise of our egalitarian society is that anyone can succeed regardless of where they are born or who their parents are.

At the heart of this national identity has been a publicly funded education system led by a professionally trained teaching workforce, offering free education to every Australian child, a public education system that served me well in my life’s journey.

I saw first-hand the best of this system as a classroom teacher working in a large secondary high school in southwestern Sydney in the 1990s. Using the Rock Eisteddfod as stimulus, we were able to bring our whole community together – students, teachers, parents and caregivers – to energise and galvanise to the delivery of a performance. We had not done anything like this before, but we called upon the expertise in dance, music, art, PDHPE, mathematics and science to design and produce a performance. I can’t tell you how proud everyone involved was, working together, acknowledging the different skills sets it took to produce.

We were an eclectic group of both staff and students, with a strong sense of the western Sydney spirit. Most students walked or bussed to the school, and many would often come early to join the breakfast program.

The opportunity to do something very different…something that stretched the imagination beyond what was ever thought possible, acted as a binding force for good.

It was a remarkable collaborative effort that engendered a strong sense of belonging, united by a common goal, and a genuine collective effort which delivered a memorable achievement for all involved and which will continue to resonate across our lifetimes.

I felt this same sense of pride when, in December 2019, I witnessed the signing of the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration by all Education Ministers.

I was proud to see both sides of politics commit to the Declaration that so many groups had made a substantive contribution to and supported the development of the Declaration.

As a country we had an agreed statement that echoed the values and beliefs of the broad education community. It was future focused and set the direction for all states and territories.

Like its predecessor The Melbourne Declaration, the Mparntwe Declaration has a clear and unambiguous focus on excellence and equity. It spoke to an explicit focus on educational disadvantage and amplified this in the following commitment to action.

“Australian Governments commit to ensuring the education community works to provide equality of opportunity and educational outcomes for all students at risk of educational disadvantage.” December 2019: p.17

Ensuring that each and every child, regardless of where they live, has access to high-quality learning environments is part of what it takes to prepare young people to participate in their communities and ensure society can benefit from the talents and skills they develop.

We know that when children, regardless of where they live, have access to high-quality learning environments, they do better in school and develop knowledge and skills that they use throughout life. Not only do students benefit, but our whole society is stronger when all students are supported within their communities to develop their skills and talents.

Five years on, the midpoint of the Declaration’s life span, and a lot has happened. A time to pause and reflect on our progress to realising the vision of a national identity set out in the Declaration and strongly underpinned by the belief our education system would deliver on a fair go for all.

Our challenge

The reality is our education system does not deliver the same educational opportunities and support for every child.

Sadly, today more children are experiencing socio-educational disadvantage than ever before. This is driven by a range of factors, including postcode, family situation and disability.

It is also true that children who need the most support are being clustered in the same schools.

This concentration of disadvantage has been noted for many years – many of you may already be familiar with it from the dynamics in your own schools and communities.

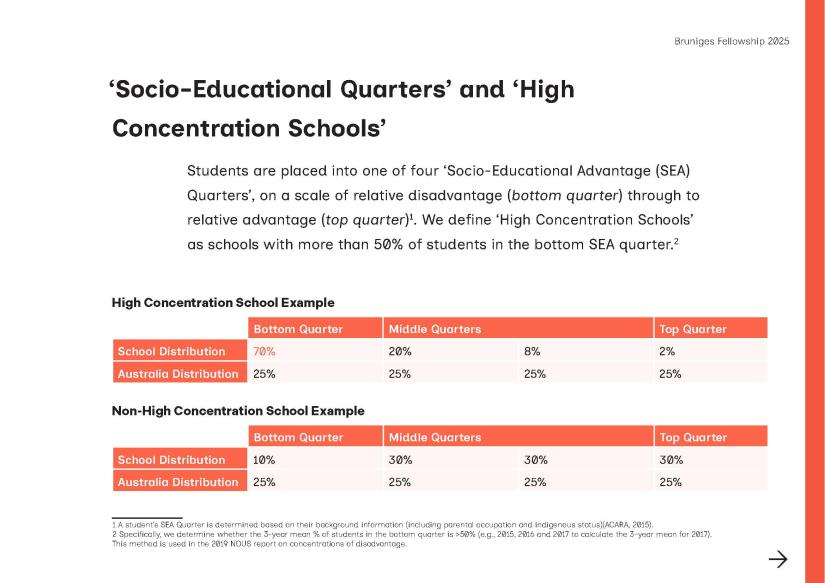

My research has sought to shine a light on what’s actually happening nationally, what the impacts are, and what can be done about it. Using the nationally agreed definition of Socio-Educational Advantage (SEA), my research defines a school with a high concentration of disadvantage as one where 50% or more of students fall in the lowest quarter of the scale.

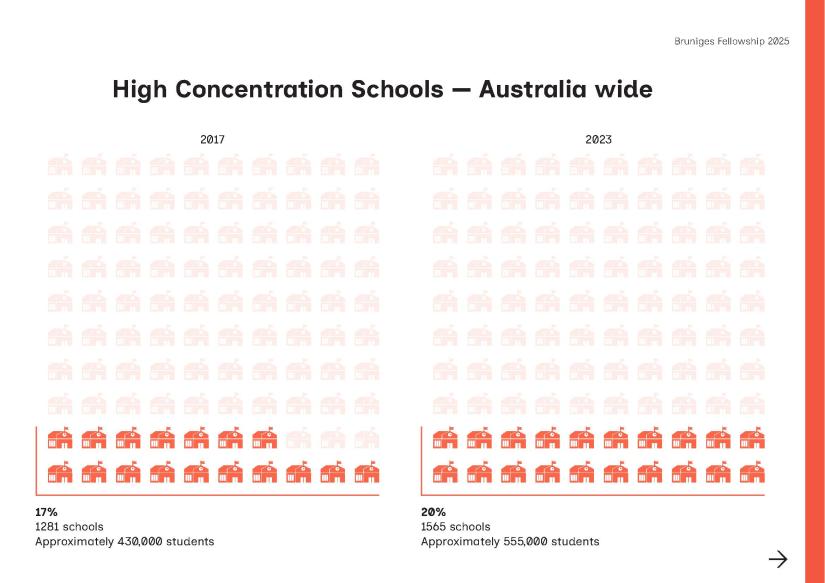

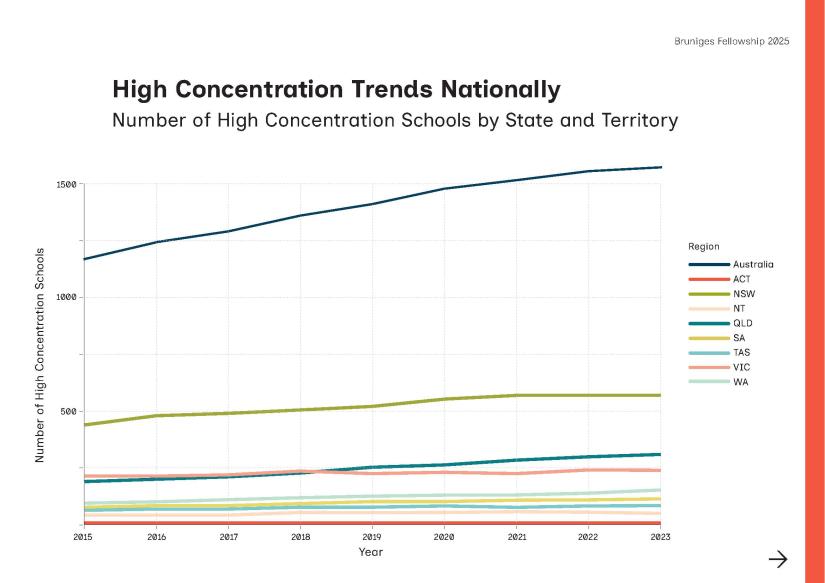

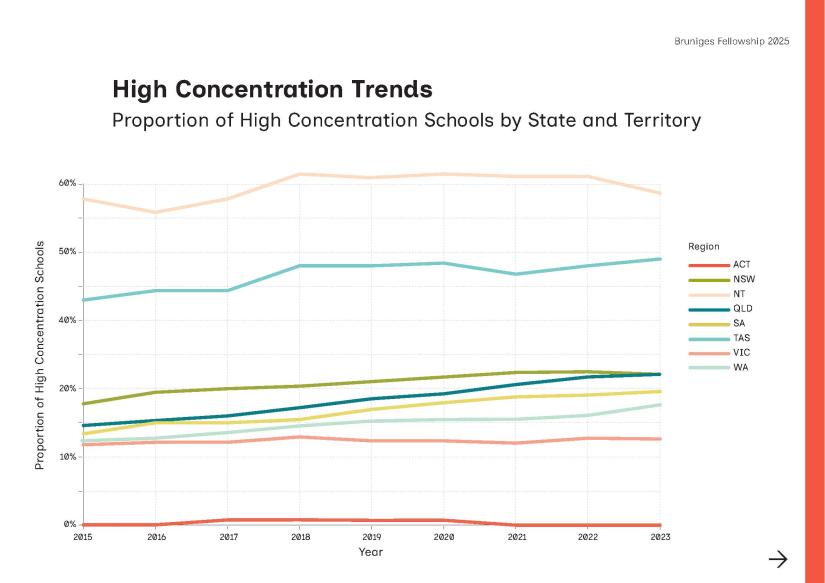

My research shows that this phenomenon is intensifying, where today we have a higher number of high concentration schools than at any time in the last decade.

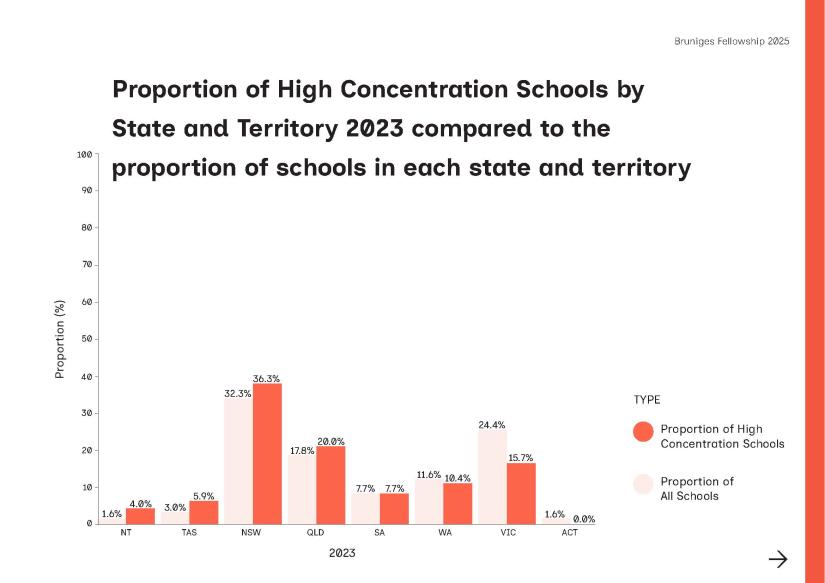

While all sectors, Catholic, Independent and Government show increasing numbers of schools in this situation, it would not be a surprise to know that public schools carry a disproportionate load of schools with this enrolment profile.

This means students who need the most support are channelled into the same schools where teachers face the most pressures.

In numbers, increasing concentrations of disadvantage looks like this (Small schools and Special schools excluded from the analysis).

In 2017, 17% or 1281 schools in Australia were classified as high concentration. This increased by 3 percentage points to 20% or 1565 schools in 2023. An increase of 284 schools.

In student numbers, in 2017 there were approximately 430k students attending a high concentration school, and by 2023 this number grew to approximately 555k students attending a high concentration school – n increase of 125k students attending a high concentration school Australia-wide in just 6 years.

As I mentioned, Government schools are overrepresented among high concentration schools. In 2023, Government schools made up 68% of all schools in Australia, yet they supported 94% of high concentration schools in Australia and in 2023, here in NSW, Government schools support 97% of high concentration schools.

The impact of this trend is that it creates a cycle of negative perceptions that undermine the bonds that tie children, their families, and their schools, to their community.

- Schools working the hardest to support those with the biggest challenges get dismissed as “bad schools”.

- Families feel they have to choose between their local school communities and educational opportunities further afield, meaning parents who can afford to move their children into other schools, often force their children to leave their communities at the time when they should be most connected.

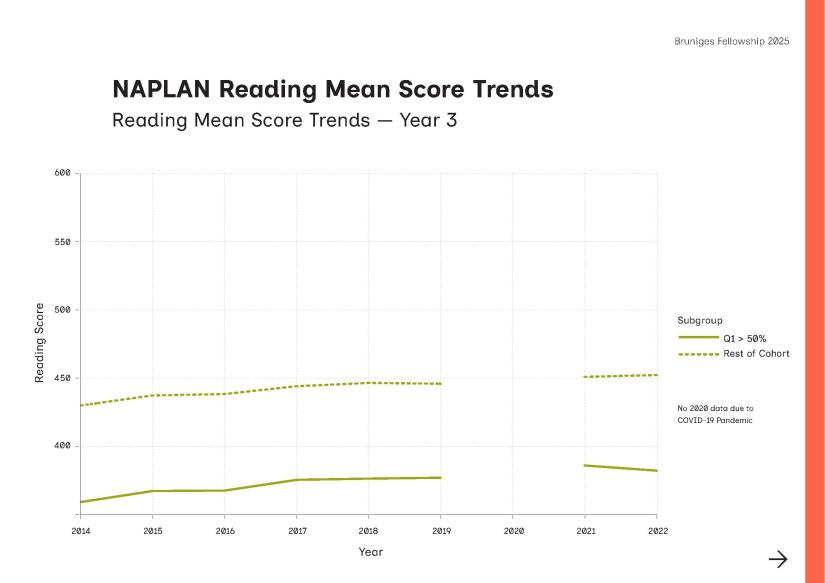

Sadly, but not surprisingly, when we examine performance measures, we see another example of the persistent link between socio-economic advantage and educational outcomes.

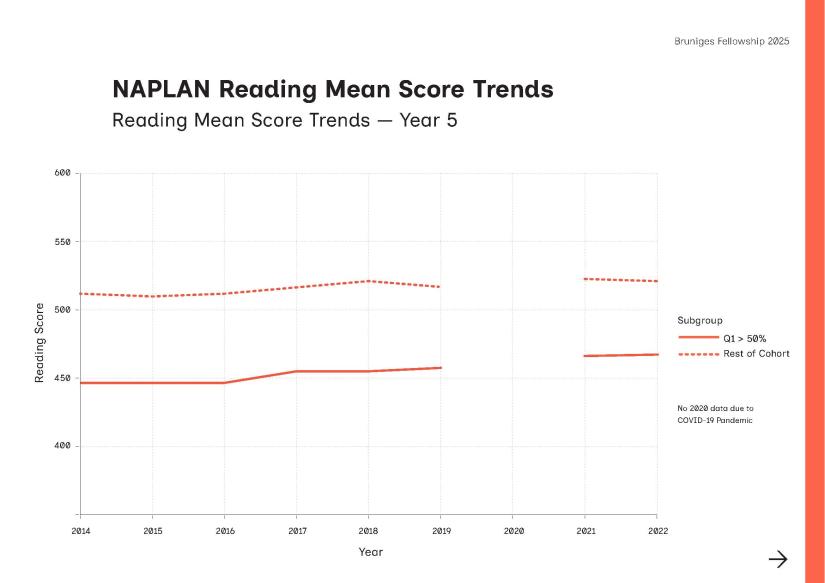

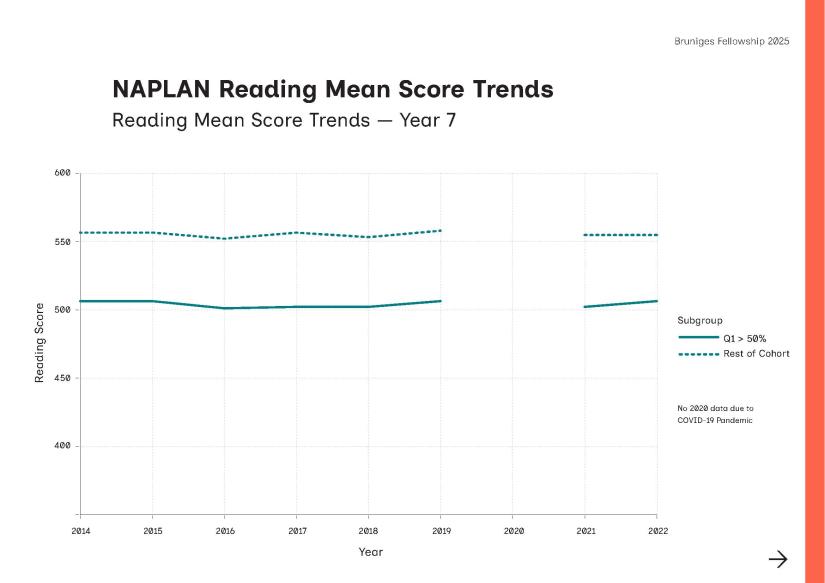

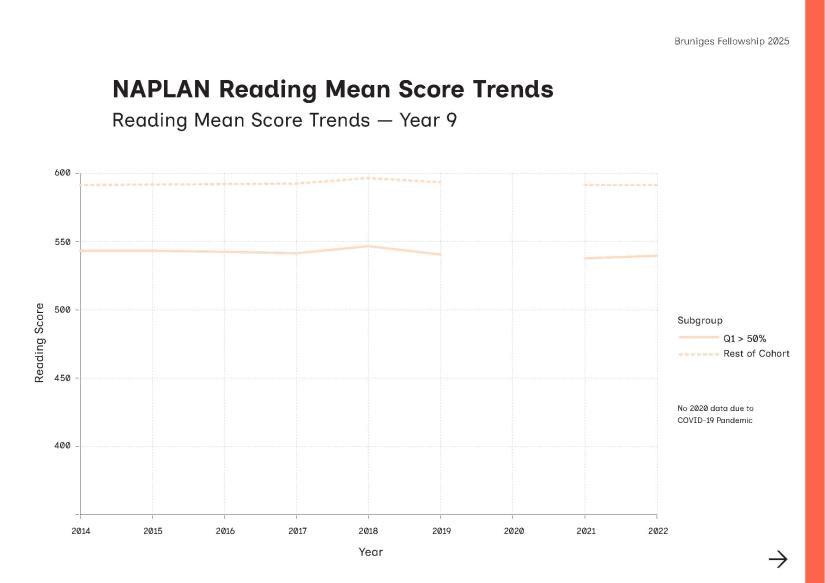

For illustrative purposes let’s look at the reading mean score trends for those schools with > 50% of their students in Q1 compared with the rest of the cohort.

This pattern is replicated across all strands (reading, writing and numeracy) and all Year levels 3, 5, 7 and 9.

Somewhere along the way our vision, the very underpinning of our national identity of a “fair go” becomes an illusion.

Our rhetoric does not reflect reality, and the key facts and findings present as a challenge for us all.

Our opportunity

The solution

It does not have to be like this.

No matter where their kids go, parents agree:

- that the education system should be fairer

- that learning in a diverse environment is critical to learning to thrive in the real world

- that schools anchored in local communities would be ideal education for their children.

Because the unfairness in our system is so embedded it will take time to address.

But if we are serious about our national self-image – if we really believe a fairer society is a better society – then we owe it to ourselves to start thinking about this seriously.

This is a complex societal challenge that requires creative and brave solutions.

There is not one answer, but there are a range of things we can do, from the local level to the national level, that could make a difference.

At a local level:

- we know that involving families in the school is critical for the learning environment, supporting schools delivering the best possible outcomes for children.

- we know that the teachers who work in these schools should be given every resource and support we can muster for them.

- we know that many kids turn up to school hungry, which affects their concentration and ability to learn. Schools should be places of learning, and supporting them to access a meal, a lunch or breakfast, can ensure they get the most out of every day of learning.

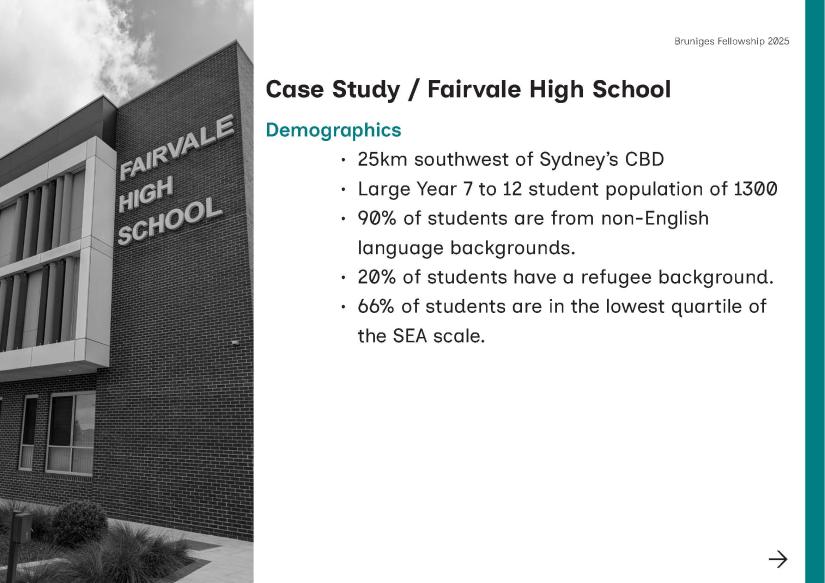

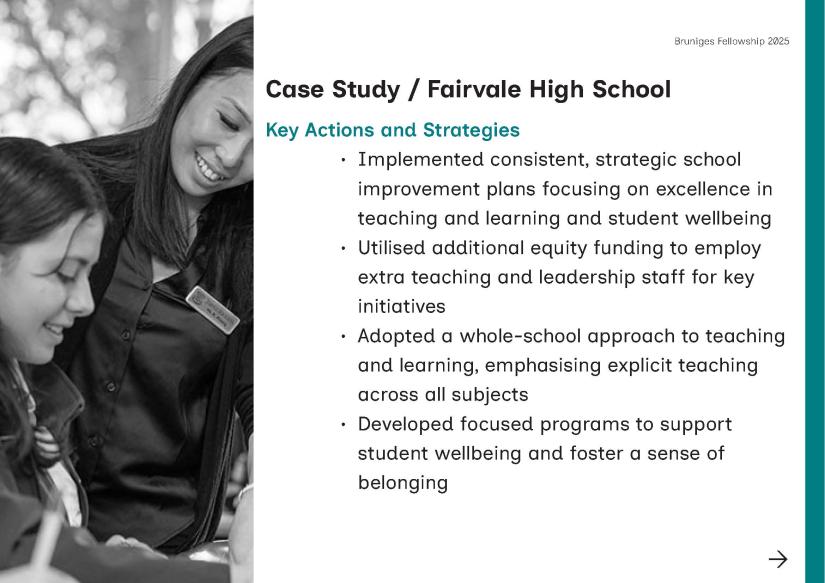

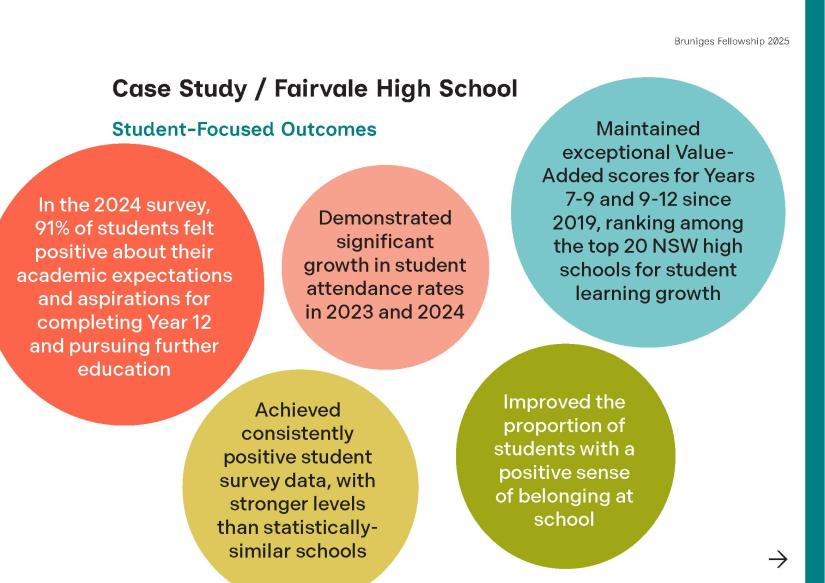

One example here in New South Wales is Fairvale High School, 25km southwest of Sydney’s CBD. 66% of its students identified as in the lowest quartile of SEA scale.

Fairvale High School has a large student population of 1300 (Year 7 to 12) and is very multicultural, including Vietnamese, Arabic, Assyrian and Pacific Island cultural groups, among many.

90% of students identify as from a language background other than English, and 20% of students are identified as coming from a refugee background.

Here there was not one program or one specific thing that turned the corner, but rather a whole school approach over a period of time that activated all layers – leadership, teaching, learning, community engagement in support of student engagement and a sense of belonging.

Another example is the Mirrung approach at Ashcroft Public School, which has been supported by NCOSS. Mirrung is a model that integrates a wider set of services into the school, with a holistic focus on meeting all the children’s needs; from food, health and wellbeing to extra-curricular activities and family supports. Cara Varian from NCOSS will be on the next panel and may like to speak more to this example.

These measures are changing outcomes and opportunities for children and families at Fairvale High School and Ashcroft Public School and the communities they are part of. However local solutions alone are not enough to address the underlying inequality that has embedded itself in our education system.

We need a broader national discussion…A national conversation that explicitly addresses growing educational disadvantage in this country. This is something that all sectors – public, Catholic, and independent – are calling for.

We know when local schools represent the local communities, in all their diversity, they create great learning environments for both academic and life skills.

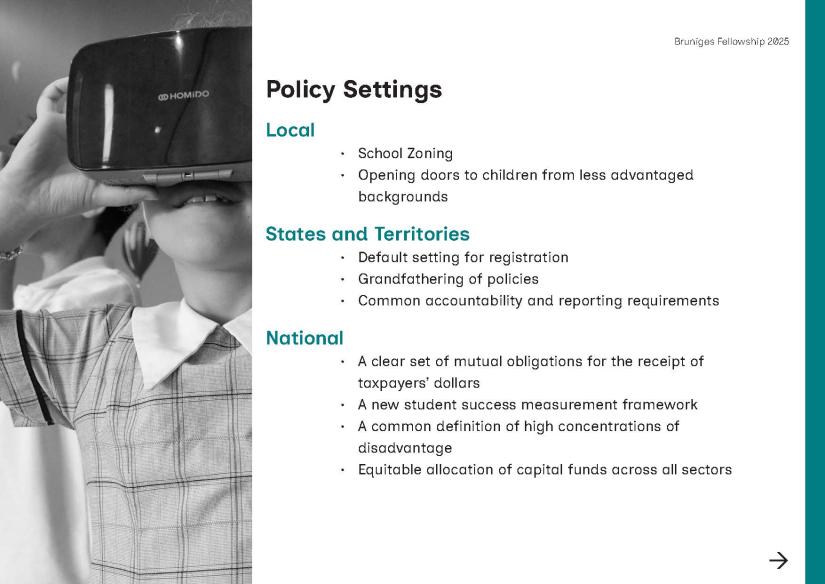

We need to think about how we encourage a trend away from concentrations of disadvantage.

- This could involve looking at school zoning – challenging the way postcode concentrates both wealth and disadvantage.

- It could involve asking more of schools that receive government funds to open their doors to children from less advantaged backgrounds – beyond the sporting scholarship.

We need to think about how state and territories policy settings can better contribute to a fair and just education system by considering aspects such as:

- A default setting for registration of all new schools to be comprehensive, not specialist or selective, with detailed consideration taking account of the impact on surrounding school SEA profiles and enrolment impact.

- Grandfathering of policies that run counter to a comprehensive school setting.

- Ensuring common accountability requirements for all schools.

The Federation delivers a complex operating context in the education field. States and territories holding the responsibility for registering and operating schools and the Federal government being the minority funder of public schools and the majority funder of the non-government sector.

This should be sorted in a way that enhances fairness and does not accelerate and compound intergenerational inequality.

At the national level, to be true to the national identity we espouse, we could pursue:

- A clear set of mutual obligations for the receipt of taxpayers’ dollars demonstrating clear public benefit and national interest.

- A new student success measurement framework could include measures of well-being, socio-educational (SEA) profiles at specified levels (school, LGA, SA2 level).

- Equitable allocation of capital funds across all sectors.

This is a challenging conversation because it lays bare the disparities, but until we find ways to connect different school communities, we will condemn our children and young people to far less. The good news is that are many opportunities for us to turn this around for the benefit of our children and our communities.

Call to action

I know these are tough conversations to have, but so important to have. Why?

- First and foremost, it matters to individuals for maximising life chances and choices.

- It matters because it adds to community cohesion, connectedness, sustainability and vibrancy.

- It matters to our nation because of the economic and social impact it has on maximising the contribution to productivity and defining the nature and type of the democratic society we wish to live in.

They challenge the baseline assumptions of our current system: that the purpose of education is the final mark, and that the parent’s responsibility is to do everything they can to ensure academic achievement.

But what if our responsibility as parents goes beyond our own child, to ensure they enter the real world, equipped with skills, connected to their community, and empowered to live their best lives.

And to ensure that life is enjoyed in a society that lives up to our national self-image, where every child has this same opportunity regardless of where they were born or who their parents are.

In 2029, when we reflect on what has been achieved in relation to the Mparntwe Declaration, my hope is that we have realised its vision for equality of opportunity and come together to put a fair go for all at the heart of education in this country.

Thank you.