- Posted on 8 Apr 2025

With the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement now a decade in operation, this UTS:ACRI Analysis provides an Australian assessment of core outcomes against a backdrop of claims by advocates and critics of the deal.

Key takeaways

- When the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement (ChAFTA) was signed in June 2015, the Australian government and business groups lauded its trade and prosperity-creating potential. ChAFTA’s passage through the Australian parliament, however, was far from straightforward. The Labor opposition initially refused to extend bipartisan support as the trade union movement criticised the deal for allegedly undermining local job opportunities and workplace safety standards. Others asserted it advanced the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) strategic interests at Australia’s expense.

- In the decade since its eventual enactment, Australia’s trade with the PRC grew from $144.8 billion to $325.5 billion, a 124.8 percent increase. This compared with 76.5 percent with the rest of the world. The PRC market has outperformed the rest of the world across both exports and imports and almost all broad categories of goods and services.

- Temporary labour migration from the PRC has fallen, both in absolute numbers and as a proportion of the total. There has been no compelling evidence presented that links unsafe workplace practices in Australia to ChAFTA’s provisions.

- Policies pursued by Canberra since 2015, under both Coalition and Labor governments, suggest that Australia’s strategic decision-making has not been compromised, despite a large and growing trade exposure to the PRC.

- The above core outcomes help to explain why a decade on Australian public support for ChAFTA remains strong.

Introduction

After 21 rounds and more than a decade of negotiations, the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement (ChAFTA) was signed in Canberra on June 17 2015 by Australian Trade and Investment Minister Andrew Robb and his counterpart from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Commerce Minister Gao Hucheng. Addressing the PRC side that had gathered there, Prime Minister Tony Abbott was exuberant:1

[W]hat you have collectively done is history making for both our countries, it will change our countries for the better, it will change our region for the better, it will change our world for the better. … We seize this opportunity of more trade and more investment with China… One day we will be able to say to our children and grandchildren, that yes, we were there the day this extraordinary agreement was signed between our two countries.

When introducing the enabling legislation to the Australian parliament on September 16 of that year, Minister Robb described it as ‘the highest quality and most liberalising trade deal that China…has done with any other developed country’, as well as ‘by far the best free trade agreement Australia has done with any country from the perspective of goods, services and investment’.2 The Business Council of Australia was similarly effusive, contending that it would ‘be transformative for the Australian economy’ by ensuring ‘a competitive edge’ for the country’s leading trade sectors.3

Advocates emphasised four key elements.

First, it contained significant tariff cuts. Data from the World Trade Organization (WTO) indicated that at the time of ChAFTA’s signing, just 8.4 percent of the PRC’s 8198 tariff lines were duty-free.4 Today the figure is not much higher at 12.1 percent.5 Yet within five years of ChAFTA’s enactment, 95 percent of PRC tariff lines were slated to be tariff-free for Australian goods. This would rise to 96.8 percent after 15 years and full implementation.6 In value terms, upon coming into force ChAFTA set tariffs at zero for 85 percent of Australian exported goods to the PRC (by 2015 value). This would rise to 93 percent by 2019 and reach 98 percent upon full implementation.7

Second, for some agricultural goods covered by PRC import quotas, like wool, Australia was extended a country-specific tariff-free allocation that would increase over time.

Third, the PRC’s market access commitments to Australia extended beyond goods to include some services. A most-favoured-nation (MFN) clause was also included in the services component of ChAFTA such that if the PRC subsequently made even more favourable market access commitments to other trade partners, then these would automatically be extended to Australian companies too.

Fourth, the inclusion of “binding” clauses meant that if Australian goods were already entering the PRC market at tariffs lower than the PRC’s WTO commitments, then the PRC could not subsequently raise them to the higher WTO level.

Yet despite its trade and prosperity-creating potential, in the months that followed ChAFTA’s signing, there looked a real possibility that its passage through the Australian parliament would be blocked. The opposition Australian Labor Party under the leadership of Bill Shorten initially declined to extend bipartisan support. Shorten labelled ChAFTA a ‘bad agreement’8 and a ‘dud deal’9, albeit emphasising that Labor remained in support of the broader principle of free trade and that ‘governments from both sides of politics’ had worked hard to land an agreement with the PRC.10

The critique was multi-pronged, but by far the most prominent criticism was around ChAFTA’s labour mobility provisions. Shorten challenged the government’s position that ChAFTA ‘will not allow unrestricted access to the Australian labour market by Chinese workers’ by pointing to clauses in the treaty that Australia would ‘not impose or maintain any limitations on the total number of visas granted’ or ‘require labor market testing, economic needs testing or other procedures of similar effects as a condition for temporary entry’.11 Labour market testing (LMT) imposes an obligation on local employers to test the availability of Australian workers before seeking to recruit them from overseas.

ChAFTA’s labour mobility provisions were described by some commentators in leading Australian media outlets as a ‘momentous concession for the Chinese’.12 Trade union leaders contended the provisions would lead to a ‘radical altering of the labour market’ and that in ‘nearly every sector of our economy…jobs will be offered to Chinese nationals rather than locals’.13 A trade union-commissioned report by an academic at the University of Adelaide concluded that ChAFTA would ‘greatly increase access’ of PRC workers to Australia.14

Aside from the number of workers from the PRC entering Australia, another claim relating to ChAFTA’s labour mobility provisions was that workplace safety standards would be eroded. This owed to a side letter in which Australia committed to removing mandatory skills testing for visa applicants from the PRC in 10 occupations, including electricians.

The national secretary of the Electrical Trades Union (ETU), Allen Hicks, said that to allow electricians from a country with an ‘appalling record on industry safety’ to practice in Australia ‘is negligent in the extreme’. Further, if we ‘just start handing licences around it’s not a matter of if, but when, someone is killed’.15 Shorten himself raised the prospect that unqualified plumbers from the PRC ‘might come and work on your house’ or PRC electricians ‘might go into your roof’.16

Another criticism, separate from those related to labour mobility, was that rather than promote risk-mitigating trade diversification, ChAFTA would instead lead to, in one commentator’s words, the PRC’s ‘economic domination’ of Australia. Beijing would then use Australia’s greater trade exposure to the PRC market to further its ‘strategic influence’ and ‘global strategic aims’.17 The PRC had already become Australia’s most important trade partner in 2007, and on the eve of ChAFTA’s signing accounted for around 30 percent of Australia’s goods exports and 22 percent of total goods and services trade.18

In 2014, former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton had warned during a visit to Australia that more trade with the PRC ‘makes you dependent, to an extent that can undermine your freedom of movement and your sovereignty, economic and political’. She also described a 630-strong Australian business delegation led by Trade Minister Robb to the PRC that year as ‘a mistake’.19

On October 21 2015, ChAFTA’s passage through the Australian parliament was finally secured. The compromise deal between the Coalition government and the opposition Labor Party involved no changes to the treaty’s text. Instead, the government agreed to three regulatory ‘safeguards’ the opposition had proposed around temporary labour migration.20

In response, Deputy Leader of the Greens Adam Bandt contended that Labor had been ‘sold a pup’ and there remained ‘a gaping hole that will allow exploitation of overseas and local workers to continue’.21 Ged Kearney, the president of the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), lamented that ‘the proposed changes simply don’t go far enough’,22 while Bob Kinnaird, a former national research director of the Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU), said Labor’s backing amounted to ‘capitulation’.23

Six months after ChAFTA’s enactment, the Sydney Morning Herald published an investigative piece professing to show how ‘Australia’s labour market and industrial system can be circumvented when free trade agreements open the nation’s markets to the world’. It homed in on seven PRC nationals, labelled ‘ChAFTA pioneers’, who had entered Australia on temporary work visas and were paid less than Australian workers and performed work in an unsafe manner.24 Associated commentary claimed this as ‘proof’ of ChAFTA’s flaws.25

The strategic critique of ChAFTA also intensified after its enactment, particularly when the legal commitments it contained proved far from fail-safe in constraining Beijing’s behaviour. Owing to a souring of political relations that began a year earlier, by the end of 2017, Beijing had ceased engaging with Canberra on ChAFTA’s institutional mechanisms, such as the various committees it established to review progress on implementation and discuss possibilities for further liberalisation.26

Reports suggesting that Beijing was disrupting trade to signal political displeasure also began appearing with increased frequency, albeit an ex-post analysis of trade data throughout 2017-2019 offered limited support for such claims.27 However, when political relations plummeted even further in 2020, Beijing responded with a clear campaign of trade punishment that saw around a dozen Australian goods having their access to the PRC market disrupted.28

Trade Minister Simon Birmingham said at the time that Beijing was acting in a way that was contrary ‘to the letter and spirit’ of its ChAFTA and WTO obligations.29 Other commentators went further, asserting that ChAFTA was ‘not worth the paper it’s written on today’.30

Now a decade in operation, and against the above backdrop of claims by advocates and critics, this UTS:ACRI Analysis provides an Australian assessment of core outcomes.31

Trade outcomes

A free trade agreement (FTA) is not a prerequisite for a strong economic relationship. That the PRC had already risen to become by far Australia’s most important trade partner in 2007 makes this plain. Nonetheless, reduced tariffs and the removal of other trade and investment barriers raises awareness of underlying economic complementarities and potentially aids households and business taking advantage of them.32

The Australian government’s own post-implementation review, released in 2021, found strong and upward- trending utilisation of ChAFTA, confirming the basic value proposition. In 2016, of the imported product lines for which ChAFTA provided a preferential tariff rate, 85.6 percent of PRC goods entering Australia (by value) did so at the reduced level.33

By 2019, ChAFTA’s utilisation rate had risen to 94.8 percent, and in 2021 it stood at 96 percent, the highest amongst all of Australia’s FTAs. Earlier data released by the PRC’s customs agencies showed that the utilisation rate of ChAFTA by PRC importers of Australian goods rose from 85 percent in 2016 to 90 percent the following year.34 The author’s understanding is that more recent PRC figures are similar to those on the Australian side.

Despite beginning from an already large base, in the decade that followed ChAFTA’s enactment Australia’s total trade with the PRC grew from $144.8 billion to $325.5 billion, a 124.8 percent increase. This compared with a 76.5 percent increase with the rest of the world.35

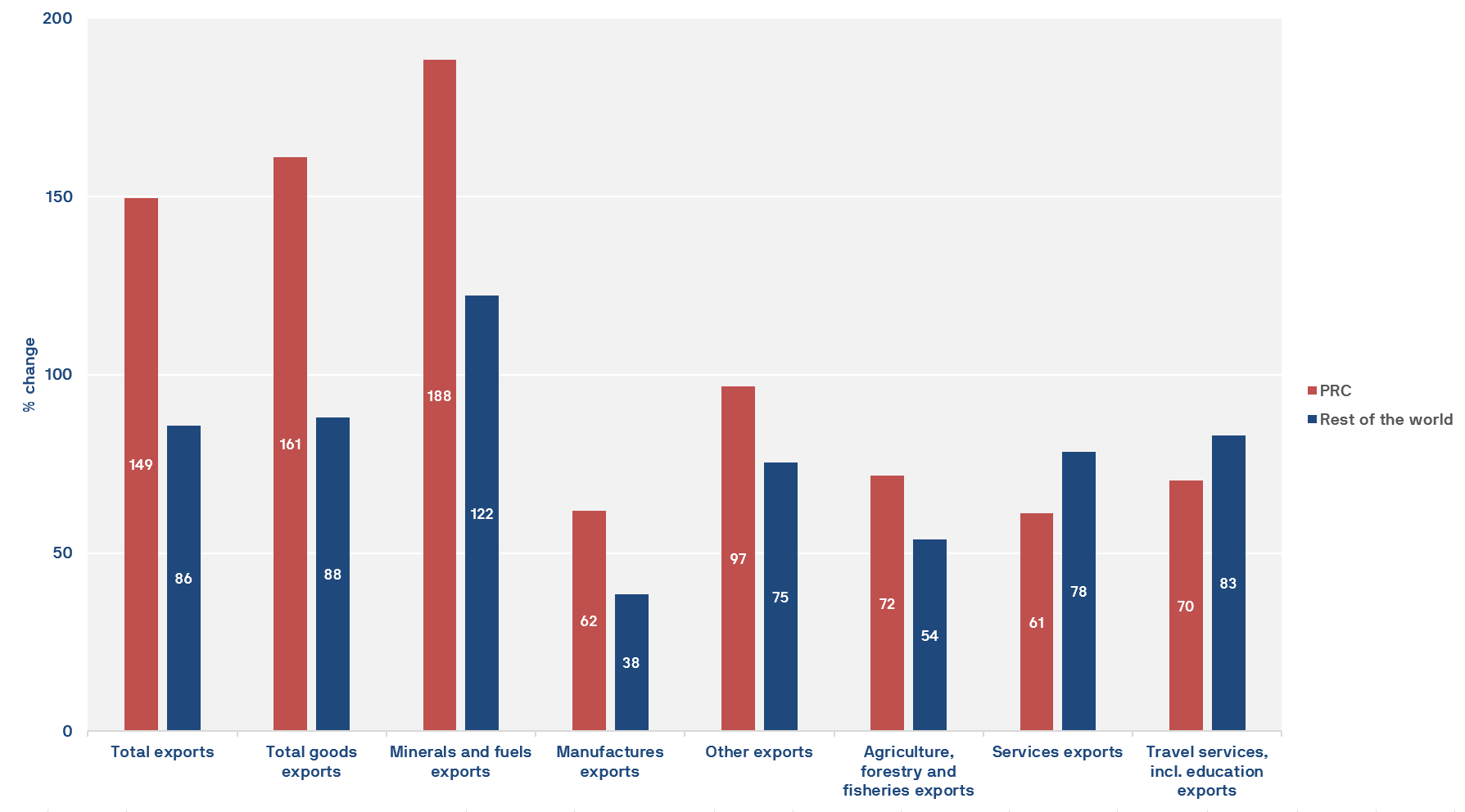

Exports rose from $85.2 billion to $212.7 billion, a 149.5 percent increase, compared with 85.6 percent to the rest of the world (Figure 1).36 The PRC market outperformed across all broad categories of goods exports. It lagged slightly on services, albeit still recorded large absolute increases. Indicative of effects favouring smaller scale operations, data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics also show the number of Australian businesses exporting to the PRC between 2014-15 and 2019-20 rose by 37.9 percent, while the number of transactions expanded by 260.0 percent.37

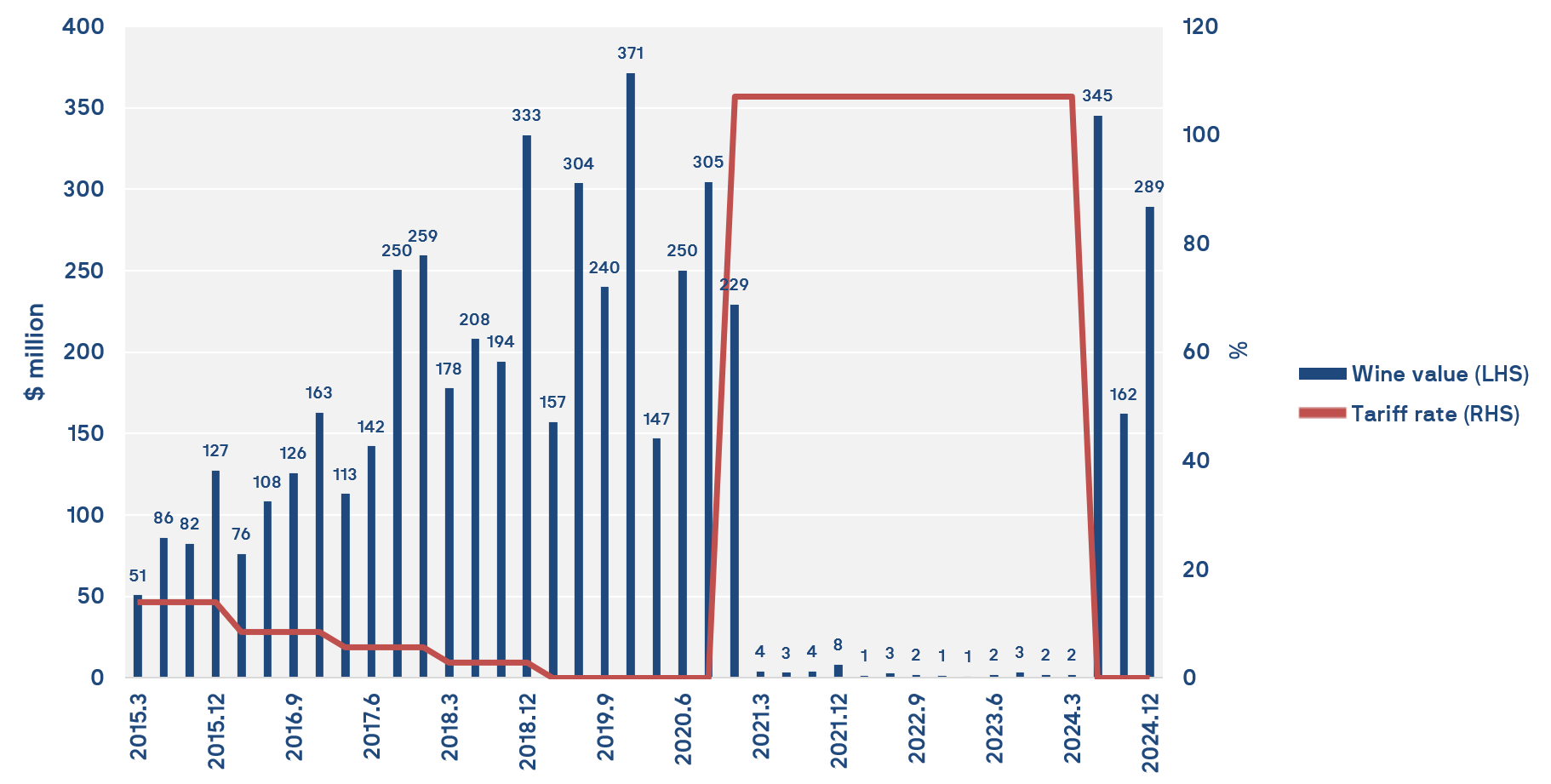

While ChAFTA was not the only driver of increased Australian exports to the PRC, it is not difficult to discern the impact that the removal and imposition of trade barriers can have at a product level. Figure 2, for example, shows the quarterly value of Australian wine exports (HS code: 220421) to the PRC trending upwards as ChAFTA led to tariffs falling from 14 percent in 2015 to zero in 2019.38 These exports then collapsed when the PRC imposed punitive tariffs on Australian wine exporters ranging from 107.1 percent to 218.4 percent in late November 2020. After these tariffs were removed in late March 2024, the trade roared back.

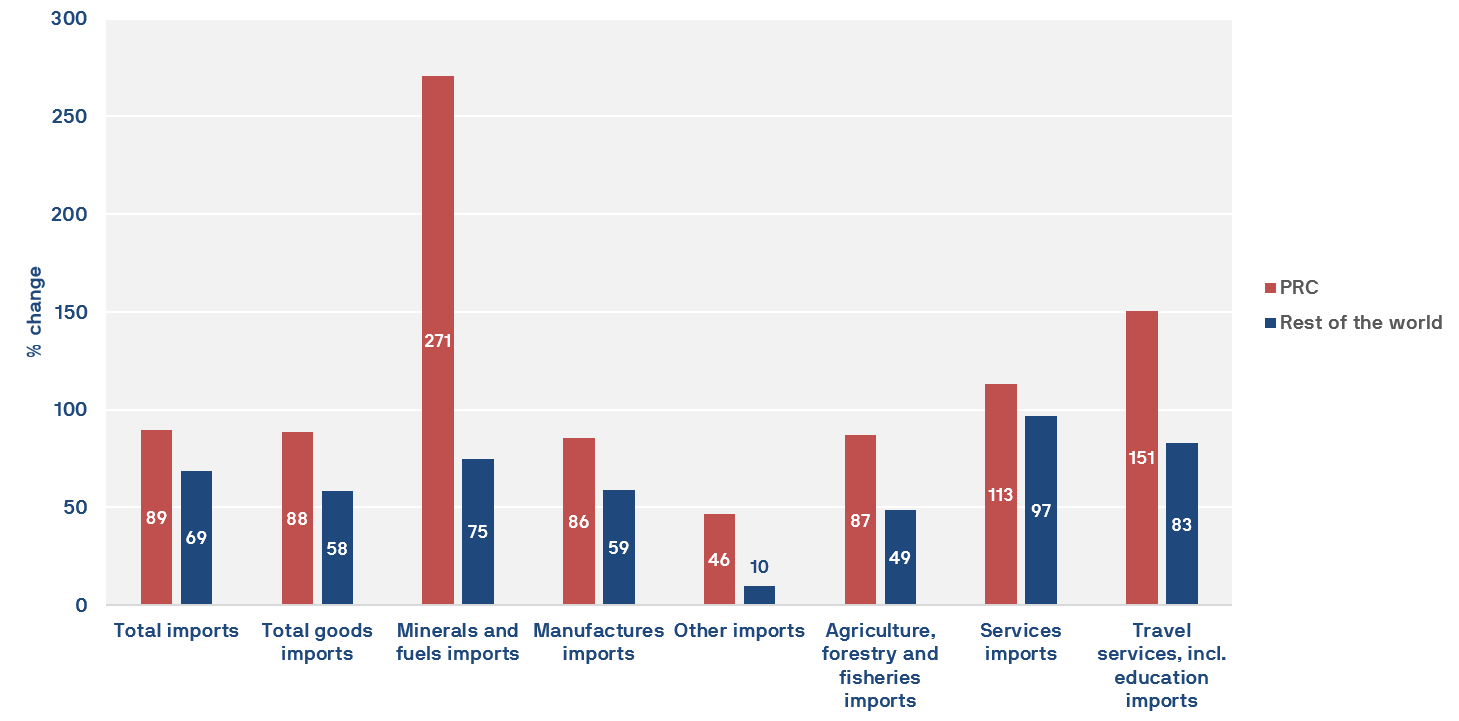

On the other side of trade equation, between 2014-15 and 2023-24 total imports from the PRC grew from $59.5 billion to $112.8 billion, an 89.5 percent jump. This compared with 68.9 percent from the rest of the world (Figure 2). The PRC market outperformed across all categories of goods and services.39

Despite the impressive trade outcomes recorded to date, scope for further trade liberalisation remains. All Australian tariffs on PRC goods were eliminated in 2019. Nonetheless, under the PRC’s WTO accession protocol, import quotas are maintained on rice, wheat, maize, sugar and vegetable oil imports, with in-quota tariffs ranging from one percent to 15 percent. ChAFTA did not provide Australian exporters of these goods with preferential market access.

Under ChAFTA, Australian beef was granted concessional tariff rates and has been able to enter the PRC tariff-free from the beginning of 2024. However, the PRC retained the right to impose “safeguard” tariffs when volumes exceed a specified level in a given calendar year. The trigger was initially set at 170,000 tonnes and rising over time to reach 249,000 tonnes in 2031. This meant that last year, for example, because the trigger was reached in September, Australian exporters faced tariffs of 12 percent from October to December.40

Labour market outcomes

In 2015, the Australian government rejected suggestions that ChAFTA would lead to a ‘radical altering’ of the Australian labour market. Analysis undertaken at the time by the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS:ACRI) largely concurred with the government’s position.41

Data are now available to adjudicate the debate. In 2014-15, 3522 primary temporary resident (skilled) visas were granted to PRC nationals (Figure 3).42 This was just a fraction (6.9 percent) of all such visas issued and was trivial in the context of total employment in Australia of nearly 12 million.43 Despite the modest starting point, and contrary to the critics’ claims, after ChAFTA was enacted both the number of visas extended to PRC nationals and their proportion of the total fell. In 2023-24, these numbers stood at just 2033 and 3.9 percent, respectively. By then, total employment in Australia exceeded 14 million.

That temporary labour migration from the PRC did not surge following ChAFTA’s enactment is, in fact, unsurprising.

First, the labour mobility provisions in ChAFTA were only modest extensions of what was already being applied. Agitation that LMT would no longer be applied to PRC nationals missed the broader context that it had been abolished from Australian legislation entirely in 2001.

As the non-partisan Migration Council of Australia explained, this was for the straightforward reason that it was found to be ineffective: ‘Malicious employers could easily sidestep such regulation while the majority of employers who acted in good faith were burdened with administration proving the job advertising requirement’.44 It was only reintroduced by the outgoing Labor government on the last parliamentary sitting day before the 2013 federal election was called. Even then, the Minister for Immigration, Brendan O’Connor, placed on the record that LMT requirements would only apply to temporary overseas workers in occupations ‘primarily at skill levels two and three’.45

In the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO) these were mostly trades-based occupations and O’Connor put their proportion at around 40 percent of the temporary labour migration program. Higher skilled occupations, such as managers and professionals, and which accounted for a majority of the program, would remain exempt. The new legislation was equipped with an instrument allowing the relevant minister to make LMT exemptions.

Prior to going into effect on November 23 2013, the incoming Minister for Immigration, Michaela Cash, issued an instrument exempting occupations at skill levels one and two, broadly as O’Connor had intended.46 Cash subsequently issued another instrument on November 6 2014 that made a series of blanket exemptions for nationals from countries with which Australia had an FTA.47

This move, seven months prior to ChAFTA’s signing, was made because it was deemed the commitments in these existing FTAs were inconsistent with requiring LMT. At the time, the list of countries that had already signed an FTA with Australia included seven of Australia’s then-top 11 trading partners – the US, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia. The PRC, despite being Australia’s largest trading partner by far, was the odd one out. In any case, in extending an exemption to PRC nationals in occupations at skill level three and below, the practical impact would barely register. In 2014-2015, there had been only 353 such visas granted to PRC nationals. This accounted for just 3.9 percent of the total. Today temporary labour migration from the PRC remains dominated by higher skill level occupations.48

Second, as was the case in many of Australia’s other FTAs, the commitments in ChAFTA were couched in terms of five specific categories of temporary entrant. These included: Business Visitors, Intra-Corporate Transferees, Independent Executives, Contractual Service Suppliers and Installers and Servicers. No Australian government would consider limiting the number of PRC nationals temporarily entering Australia on a business visa.

Similarly, the University of Adelaide academic that had warned ChAFTA would ‘greatly increase access’ of PRC workers to Australia accepted that exemptions from LMT for Intra-Corporate Transferees and Independent Executives were ‘reasonable’.49 Certainly, Australian companies would expect to have the right to freely transfer their staff and executives to establish or work in their existing operations in the PRC. In fact, Australia had long ago extended an exemption from LMT to executives and senior managers of companies from the WTO’s 164 members.50

This left just two categories of potential concern. A Contractual Services Provider is defined as someone ‘who has trade, technical and professional skills and experience and who is assessed as having necessary qualifications, skills and work experience accepted as meeting Australia’s standards for their nominated occupation’.

Their visa possibilities, however, are limited to circumstances where they are an employee of a PRC company contracted to supply a service within Australia, and which does not have a commercial presence or where they are engaged by a company that does. Contractual Service Suppliers had also already been exempted from LMT in previous FTAs with New Zealand, Thailand, Chile, Korea and Japan. In none of these cases had there been a subsequent flood of temporary labour migration.

As for Installers and Servicers, such visas were limited to installing and/or servicing machinery and equipment when such tasks are a condition of purchase. Their entry was also restricted to being less than three months.51

Third, ChAFTA contained an overarching labour market protection. This said that Australia’s grant of temporary entry would be contingent on meeting eligibility requirements within Australia’s migration law and regulations ‘as applicable at the time of an application’. Even ChAFTA’s critics conceded this meant that after ChAFTA’s enactment there remained ‘sufficient flexibility and scope…to include labour market testing…’.52

Finally, Australia’s existing laws – specifically, the Worker Protection Act 2008 – meant that companies would still have to offer foreign workers the same wages and conditions as local workers, reducing any incentive for employers to wade through the fees and administrative processes necessary to access overseas workers.

Much was made of a memorandum of understanding (MoU) signed alongside ChAFTA that referenced investment facilitation agreements (IFAs). These opened the possibility of a PRC company investing $150 million or more in a large-scale infrastructure project negotiating with the then-Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) (now the Department of Home Affairs) a labour agreement that, once in effect, would provide certainty and streamline the process for bringing in overseas workers.

A clause in the MoU stated that LMT would not be required ‘to enter into an IFA’.53 However, what went unmentioned in criticisms levelled at the MoU was that this clause was quickly followed by a clarification stating that, once executed, ‘A labour agreement will be entered into…including any requirements for labour market testing’. An IFA requires the China International Contractors Association to approach the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) in the first instance to assess whether a proposal meets the criteria laid out in the MoU. The author’s understanding is that no such approaches have been made. The MoU raising the prospect of IFAs was also separate to the text of ChAFTA and its side letters, connoting that it did not form part of Australia’s international treaty obligations.

Claims that ChAFTA would also erode workplace safety standards were similarly not situated in the requisite context. While committing to remove mandatory skills testing for visa applicants from the PRC in 10 occupations, including electricians, there were 20 other occupations that remained unaffected. More importantly, what the change did was simply bring the PRC into line with the way that temporary labour migration visa applications were processed from more than 150 other countries.

Previously, the PRC had been on a list of just 10 countries whose citizens were subject to mandatory rather than discretionary skills assessments. An electrician from Kazakhstan, Kenya or Korea, for example, never had to worry. When a senior DIBP official was asked by the Joint Standing Committee on Treaties whether the PRC possessed ‘any other risks compared with those other 150 countries’, the answer was ‘no’.54 The DIBP further confirmed that while it would no longer be a routine part of the visa application process, the assessing officer could still require a verification of skills if they considered it necessary.

Upon arrival, an electrician from the PRC, just like those from more than 150 other countries, would need to satisfy any licensing and registration requirements at the federal and state levels, including passing any tests and skills assessments, before performing work. Otherwise, their visa would be cancelled after 28 days. In every year since 2014-15 the number of PRC electricians granted temporary work visas has been less than five.55

The Sydney Morning Herald investigation referencing the activities of seven ‘ChAFTA pioneers’ as evidence of shortfalls in ChAFTA’s labour market provisions was also a distortion. What it revealed was troubling but unrelated to ChAFTA. The PRC workers had entered Australia on sub-class 400 visas. These existed long before ChAFTA and only allowed entry for very specific purposes and non-ongoing work.

In the case highlighted by the Herald, an Australian company had bought a car park stacking machine from a PRC company, and some of the PRC company’s workers were granted temporary entry to assist with its installation. A different Australian service provider had issued them with worksite safety certificates in a dubious manner and there had been a lack of adherence to other existing laws and regulations, such as around remuneration. The PRC workers were sent home before the installation was complete owing to a lack of compliance with workplace safety protocols and local workers completed the job.

A skirting of procedures and rules needed to be guarded against before ChAFTA and the same is true today. The markedly few temporary labour migration visas given to PRC nationals, however, makes clear that any such skirting is far from widespread.

Strategic outcomes

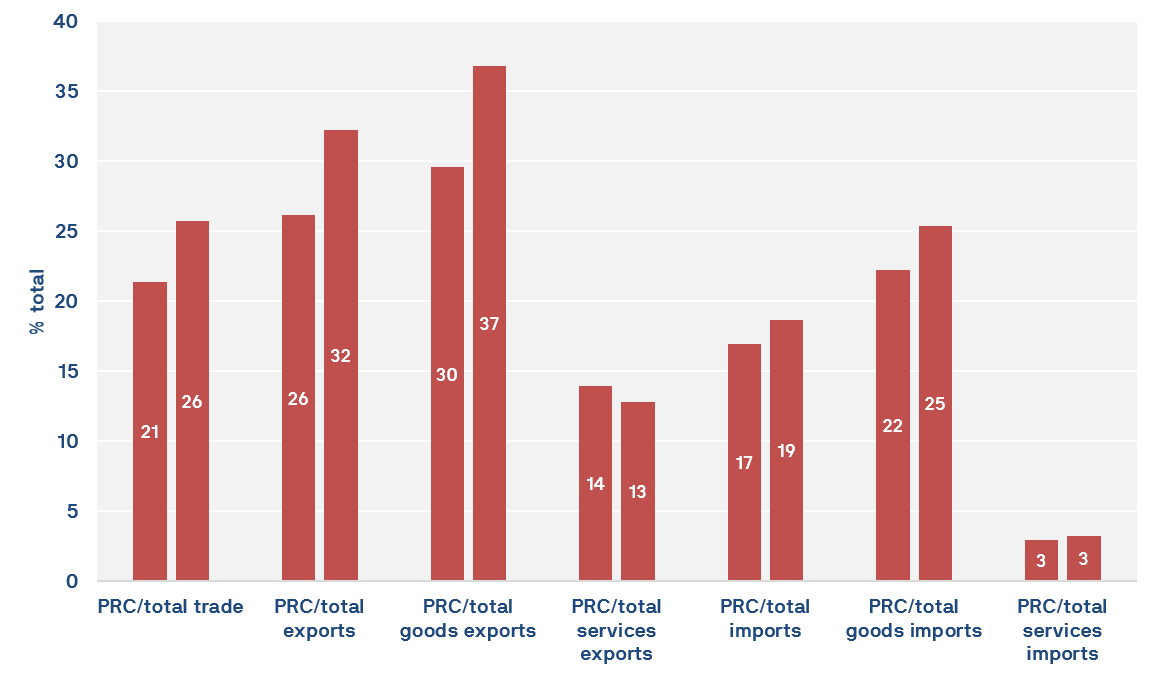

After ChAFTA was enacted, Australia’s trade with the PRC increased as a proportion of the total, from 21.4 percent in 2014-15 to 25.7 precent now (Figure 5).56 Apart from services exports, the PRC’s share increased across both imports and exports and all broad categories of goods and services. That said, it would be difficult to make the case that ChAFTA has seriously distorted Australia’s geographic trade playing field. This is because by 2023-24 Australia had FTAs with its top 11 trading partners, which collectively accounted for 71.5 percent of total trade.57

Nonetheless, there remains the question of whether a large trade exposure has conferred on Beijing an ability to exert ‘economic domination’ and advance its ‘strategic interests’ at Australia’s expense. There is little evidence to support an assessment that it has.

From a PRC perspective, one of the benefits ChAFTA foreshadowed was liberalised access to Australian assets for PRC investors. Yet beginning in 2016, Canberra began blocking PRC investment proposals with greater frequency, including deals that had no obvious connection to national security risks.58 Canberra also took a prominent position in supporting an international arbitration decision that declared PRC activities in the South China Sea to be illegal under international law.

In 2017, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull again riled Beijing by citing ‘disturbing reports about Chinese influence’ when introducing tough new foreign interference laws.59 Beijing responded by putting Australia in the diplomatic deep freeze, including by refusing to issue visas for government ministers.60 However, this did not stop Australia from leading the world the following year in banning PRC technology companies from participating in its 5G telecommunications rollout.61 When political relations collapsed in 2020, Beijing responded not only by cutting off senior political dialogue but also embarking on a campaign of trade punishment.

Yet Australia still did not adjust policy course. In fact, if anything, it spurred a stronger balancing impulse in its foreign policy settings with Canberra working more closely with Washington and other regional partner capitals, like Tokyo and New Delhi. In May 2020, the same month Beijing imposed prohibitive tariffs on Australian barley exports worth around $1 billion, the Coalition government under Scott Morrison set in motion the events that would culminate in the signing of the AUKUS partnership with Washington and London the following year62 to bolster military deterrence against the PRC.63

Since its election in May 2022, the Labor government under Anthony Albanese has not reversed any substantive policy position taken by previous Coalition governments related to the challenges that the PRC presents to Australia’s interests. Indeed, in some areas, such as contesting Beijing’s influence efforts in the South Pacific, it has been more active.

In October 2024, Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs Simon Birmingham acknowledged and endorsed the government’s policy continuity.64 The Albanese government’s critics nowadays mostly reproach it for what they perceive to be the avoidance of new policy actions that could jeopardise the recently restored trade links with the PRC. One example is the government’s decision in October 2023 to allow a PRC company to retain the lease to operate Darwin Port.65 However, the previous Morrison government had also come to the same decision during its tenure. This followed advice from the Department of Defence that there were no national security reasons for recommending taking such a step.66

Similarly, the government has been criticised in some quarters for refraining from placing sanctions on PRCgovernment officials implicated in human rights abuses. The Morrison government had elected not to do so as well, albeit Morrison has since contended this was because his government ran out of time before the 2022 election was called.67

Another example is that some members of the opposition have criticised the government for brokering deals around the removal of barley and wine tariffs rather than insisting that the WTO delivers an adverse public judgement against the PRC. However, the relevant opposition shadow ministers for foreign affairs and trade supported the Albanese government’s approach owing to it bringing faster relief to Australian exporters.68

What Labor has changed to pursue its policy of stabilisation with the PRC is to abandon the Morrison government’s muscular rhetoric. It has also instituted messaging discipline such that commentary around relations with the PRC is overwhelmingly delivered by Albanese himself and Foreign Minister Penny Wong. This does not equate to what some observers have deemed ‘public silence’, however.69

Little is more public than a media release and at the time of writing, Wong has issued at least 34 statements critical of Beijing during her tenure as Foreign Minister, a rate of one a month, covering topics from Australians detained in the PRC, human rights abuses inflicted on the PRC’s ethnic minorities and instances where Canberra regards Beijing as having not acted in accordance with international law.70

Shadow Foreign Minister Birmingham has also stated that while a Peter Dutton-led Coalition government would not shy away from being ‘clear, firm, [and] consistent’ with Beijing, it recognised that ‘rhetoric and tone’ were integral to ‘good diplomacy’. In handling the PRC relationship, the Coalition would aim for ‘coordination and consistency’ and ‘apply as much unity as possible’.71

A strong case can be made that the experience of being targeted with PRC trade punishment has, in fact, bolstered Canberra’s confidence in staying the strategic policy course, even as aggregate trade exposure to the PRC remains high.72 One of the key lessons the episode confirmed was Beijing’s unwillingness to disrupt many big-ticket items, like iron ore, liquified natural gas, lithium and wool. This can be attributed to the fact that the PRC needed Australia as a supplier as much as Australia needed the PRC as a market.

Most of the Australian industries that Beijing could strike at acceptable cost to the PRC’s own interests were also readily able to mitigate the impact. Goods such as coal and barley, for example, are traded in open and competitive global markets. When access to the PRC was blocked, these markets quickly redirected Australian supply elsewhere. That a couple of industries, such as wine and lobster, were harder hit and have rushed back to the PRC when the disruptive measures were eventually removed does not reflect naivety around geopolitical risk.

How could winemakers diversify away from the PRC when demand from Australia’s second and third largest markets, the US and the UK, has been falling since 2020? How could Australia’s live rock lobster exporters diversify their sales when the PRC accounts for 90 percent of global imports? The PRC also avoided disrupting Australian supply chains. To do so would cost PRC exporters sales in the short run and incentivise the emergence of alternative supply chains that would further damage the PRC’s interests in the longer run.

Further, the PRC has its own supply chain fears. In 2023, Australia ranked the PRC’s fifth largest import source. Its other leading sources were also on the opposing side of the geopolitical spectrum – Taiwan, the US, Korea and Japan.73

That ChAFTA fell short of constraining Beijing’s behaviour entirely does not support an assessment that it is ‘not worth the paper it’s written on’. Even as Beijing implemented a campaign of trade punishment, most Australian goods continued to enter the PRC market at lower tariff rates than their international competitors.

Similarly, Beijing continued to implement tariff reductions that were scheduled in ChAFTA. By way of illustration, in 2024 the remaining tariffs on beef, cheese, butter and yoghurt were eliminated and the country-specific, tariff-free quota allocation on Australian wool exports was again increased on schedule.74

It proved the case, too, that Beijing remained, at least in some respects, more sensitive to being seen to adhere to international trade rules than the world’s other superpower. In three of their recent bilateral trade disputes, both Australia and the PRC agreed to defer to an independent adjudicator.

The timelines in these disputes are revealing. In the case of barley, for example, Australia requested a WTO panel be established in March 2021. The panel’s final report was circulated to both parties in March 202375 – reportedly in Australia’s favour.76 The next month Canberra and Beijing announced a deal had been struck in which Beijing would undertake an ‘expedited review’ of the tariffs it had imposed. This led to them being lifted in August.77 Australia then withdrew the case but not without Foreign Minister Wong expressing that Australia ‘would not have been able to get this outcome without working through the WTO’.78

After a six-year hiatus, Beijing has also begun re-engaging with ChAFTA’s institutional mechanisms. On April 16 2024, a second meeting of the Joint Commission overseeing ChAFTA’s implementation was held in Canberra. Seven of the eight ChAFTA committees have also met with the exception being the Committee on Technical Barriers to Trade.79

Conclusion

While some initial ChAFTA advocacy may have been excessively exuberant, this UTS:ACRI Analysis has shown that Australia’s trade and prosperity received a boost, while the claims advanced by the deal’s critics have overwhelmingly not materialised. In the case of those around ChAFTA’s labour mobility provisions, data over the past decade point in precisely the opposite direction.

The Australian public have also delivered their verdict. At the end of 2014, shortly after it was announced that ChAFTA negotiations had reached a successful conclusion but before the text was released, the public were broadly supportive with 44 percent approving of signing the deal, while 18 percent registered disapproval.80

After the campaign against ChAFTA gathered pace, however, the numbers narrowed. A poll conducted the following August found 40 percent thought it was ‘a good thing’, while 31 percent did not.81 Two months earlier the CFMEU had contended there was 90 percent opposition.82 Following ChAFTA’s enactment, however, public opposition receded. An April 2017 poll found a higher proportion of Australians looked upon increased trade with the PRC more favourably than with the US.83

Even during the depths of Beijing’s campaign of trade punishment against Australia in 2021, nationally representative polling by UTS:ACRI found that 52.3 percent of Australians considered that ChAFTA had been beneficial for Australia, compared with just 12.5 percent that disagreed with the proposition. These percentages remained consistent throughout 2022-2024.84 Australians continue to harbour many concerns about the PRC’s rise. Evidently however, ChAFTA is not one of them.

Endnotes

1. Tony Abbott, ‘Address to the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement signing ceremony luncheon’, speech, Canberra, June 17 2015 <https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/release/transcript-24543>.

2. House of Representatives, Official Hansard, Parliament of Australia, September 16 2015 <https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22chamber/hansardr/842ee7d9-89d4-4e4f-bc93-045b018bbeb2/0000%22>.

3. Business Council of Australia, ‘A business case for ChAFTA’, media release, September 18 2015 <https://www.bca.com.au/a-business-case-for-chafta>.

4. James Laurenceson, ‘How good is the TPP? Look to China for an answer’, ABC News, May 22 2015 <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-05-22/laurenceson-how-good-is-the-tpp-look-to-china-for-an-answer/6489262>.

5. World Trade Organization (WTO), ‘Tariff analysis online’, accessed January 29 2025 <https://tao.wto.org/welcome.aspx?ReturnUrl=%2f>.

6. Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, ‘Interpretation for the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement’, June 19 2015 <https://english.mofcom.gov.cn/Policies/PolicyInterpretation/art/2015/art_ceaa6285302c4a3f8f8d84101eedea26.html>.

7. Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ‘Guide to using ChAFTA to export and import’, accessed January 29 2025 <https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/chafta/doing-business-with-china/guide-to-using-chafta-to-export-or-import>.

8. Bill Shorten, ‘PM's free trade deal threatens local job opportunities’, The Australian, July 22 2015 <https://www.theaustralian.com.au/opinion/bill-shorten-pms-freetrade-deal-threatens-job-opportunities/news-story/07b2c1b30e92f14e791734c8b7b03ea4>.

9. Mark Kenny, ‘China-Australia free trade agreement a dud deal: Bill Shorten’, Sydney Morning Herald, September 3 2015 <https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/chinaaustralia-free-trade-agreement-a-dud-deal-bill-shorten-20150903-gjej01.html>.

10. Bill Shorten, ‘Labor supports free trade, so let’s get ChAFTA right’, ABC News, September 4 2015 <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-09-04/shorten-labor-supports-free-trade,-so-lets-get-chafta-right/6748830>.

11. Bill Shorten, ‘PM’s free-trade deal threatens local job opportunities’, The Australian, July 22 2015 <https://www.theaustralian.com.au/opinion/bill-shorten-pms-freetrade-deal-threatens-job-opportunities/news-story/07b2c1b30e92f14e791734c8b7b03ea4>.

12. Bob Kinnaird and Bob Birrell, ‘Under free trade agreement, Chinese workers can avoid labour-market tests’, Sydney Morning Herald, September 3 2015 <https://www.smh.com.au/opinion/under-free-trade-agreement-chinese-workers-can-avoid-labourmarket-tests-20150901-gjc8ca.html>.

13. Dan Conifer, ‘Free trade agreement: Voters oppose China-Australia deal after hearing controversial elements: poll’, ABC News, June 24 2015 <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-06-24/voters-oppose-china-australia-fta-due-to-controversial-elements/6568210>.

14. Joanna Howe, ‘The impact of the China-Australia free trade agreement on Australian job opportunities, wages and conditions’, University of Adelaide, October 6 2015 <https://apo.org.au/node/57710>.

15. Joanna Mather, ‘China FTA skills test waiver alarms unions’, The Australian Financial Review, June 29 2015 <https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/china-fta-skills-test-waiver-alarms-unions-20150628-ghztkg>.

16. Senate, Official Hansard, Parliament of Australia, September 9 2015 <https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/chamber/hansards/820db5aa-c56f-465a-b752-6dd3b2287236/toc_pdf/Senate_2015_09_07_3668_Official.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf>.

17. Geoff Wade, ‘Are we fully aware of China’s ChAFTA aspirations?’, ABC News, December 1 2015 <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-12-01/wade-are-we-fully-aware-of-chinas-chafta-aspirations/6985770>.

18. Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ‘Direction of goods and services trade’, accessed January 29 2025 <https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/trade-and-investment-data-information-and-publications/trade-statistics/trade-time-series-data>.

19. Paul McGeough, ‘Hillary Clinton criticises Australia for two-timing America with China’, Sydney Morning Herald, June 27 2015 <https://www.smh.com.au/world/hillary-clinton-criticises-australia-for-twotiming-america-with-china-20140627-zso6c.html>.

20. Phillip Coorey, ‘ChAFTA: China free trade deal to pass after Labor deal’, The Australian Financial Review, October 21 2015 <https://www.afr.com/politics/chafta-china-free-trade-deal-to-pass-after-labor-deal-20151021-gke8uz>.

21. Daniel Hurst, ‘Labor and Coalition reach agreement on China-Australia free trade deal’, The Guardian, October 21 2015 <https://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/oct/21/labor-and-coalition-reach-agreement-on-china-australia-free-trade-deal>.

22. Phillip Coorey, ‘ChAFTA: China free trade deal to pass after Labor deal’, The Australian Financial Review, October 21 2015 <https://www.afr.com/politics/chafta-china-free-trade-deal-to-pass-after-labor-deal-20151021-gke8uz>.

23. Bob Kinnaird, ‘The price of Labor’s capitulation on ChAFTA’, Pearls and Irritations, November 11 2015 <https://johnmenadue.com/bob-kinnaird-the-high-price-of-labors-capitulation-on-chafta/>.

24. Adele Ferguson and Sarah Danckert, ‘ChAFTA has opened door to unqualified workers’, Sydney Morning Herald, June 3 2016 <https://www.smh.com.au/business/workplace/chafta-has-opened-door-to-unqualified-workers-20160603-gpajfz.html>; Adele Ferguson and Sarah Danckert, ‘Dodgy safety certificates under China Australia Free Trade Agreement’, Sydney Morning Herald, June 3 2016 <https://www.smh.com.au/business/workplace/no-safety-wage-harness-under-china-australia-free-trade-agreement-20160603-gpakxm.html>.

25. Joanna Howe, ‘New visas threaten Australian jobs’, Sydney Morning Herald, June 6 2016 <https://www.smh.com.au/opinion/new-visas-threaten-australian-jobs-20160606-gpchab.html>.

26. Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ‘ChAFTA committee meetings’, accessed January 29 2025 <https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/chafta/news/implementation/chafta-committee-meetings>.

27. James Laurenceson, Michael Zhou and Thomas Pantle, ‘Interrogating Chinese economic coercion: the Australian experience since 2017’, Security Challenges, 16(4) (2020), pp. 3-23.

28. Weihuan Zhou and James Laurenceson, ‘Demystifying Australia-China trade tensions’, Journal of World Trade, 56(1) (2022), pp. 51-86.

29. Daniel Hurst, ‘Australia accuses China of breaching free trade deal by restricting imports’, The Guardian, December 9 2020 <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/dec/09/australia-accuses-china-of-breaching-free-trade-deal-by-restricting-imports>.

30. Daniel Hurst, ‘Australia cannot walk away from its free trade agreement with China, Labor says’, The Guardian, December 3 2020 <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/dec/03/australia-cannot-walk-away-from-its-free-trade-agreement-with-china-labor-says>.

31. A PRC assessment of ChAFTA’s outcomes would likely adopt different assessment criteria. For example, whereas ChAFTA promised lower PRC tariffs on Australian goods, for the PRC it foreshadowed Australia not discriminating against PRC goods in the approach taken on anti-dumping actions, as well as liberalised access for PRC investors to Australian assets.

32. Australian Government Productivity Commission, ‘Inquiry into the understanding and utilisation of benefits under Free Trade Agreements – Productivity Commission submission’, June 2024 <https://www.pc.gov.au/research/supporting/understanding-free-trade-agreements/understanding-free-trade-agreements.pdf>.

33. Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, China-Australia Free Trade Agreement Post Implementation Review, March 2 2021 <https://oia.pmc.gov.au/published-impact-analyses-and-reports/china-australia-free-trade-agreement-post-implementation>.

34. Ibid.

35. Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ‘Australia’s direction of goods and services trade – financial years from 2006-7 to present’, accessed March 3 2025 <https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/trade-and-investment-data-information-and-publications/trade-statistics/trade-time-series-data>.

36. Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ‘Australia’s direction of goods and services trade – financial years from 2006-7 to present’, accessed March 3 2025 <https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/trade-and-investment-data-information-and-publications/trade-statistics/trade-time-series-data>; Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ‘Trade statistical pivot tables’, accessed January 29 2025 <https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/trade-and-investment-data-information-and-publications/trade-statistics/trade-statistical-pivot-tables>; Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘International trade: Supplementary information, financial year’, December 12 2024, accessed January 29 2025 <https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/international-trade/international-trade-supplementary-information-financial-year/latest-release>.

37. Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Characteristics of Australian exporters’, April 27 2022, accessed January 29 2025 <https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/international-trade/characteristics-australian-exporters/latest-release>. Note: Data after 2019-20 are unavailable.

38. International Trade Center, ‘International Trade Map’, accessed March 4 2025 <https://www.trademap.org/Index.aspx?>.

39. See footnote 36.

40. Fiona Myers, ‘Beef stir as China quota hit’, The Weekly Times, October 16 2024 <https://www.weeklytimesnow.com.au/news/australias-beef-imports-to-china-reach-trigger-limit/news-story/58231768b8f7cb1f764ceca3000266cb>.

41. James Laurenceson, ‘China free trade agreement: baseless fears on labour are holding up progress on historic deal’, Daily Telegraph, July 28 2015 <https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/opinion/china-free-trade-agreement-baseless-fears-on-labour-are-holding-up-progress-on-historic-deal/news-story/1fd03f955ab585f2c0606cedf98b8d9e>; James Laurenceson, ‘China-Australia FTA concerns unwarranted’, The Australian Financial Review, September 7 2015 <https://www.afr.com/policy/chinaaustralia-fta-concerns-unwarranted-20150906-gjg9bi>; James Laurenceson, ‘Labor finally puts China trade ahead of its squeaky wheels’, The Australian Financial Review, October 20 2015 <https://www.afr.com/policy/labor-finally-puts-china-trade-in-front-of-its-noisy-special-interests-20151015-gk9hse>.

42. Australian Government Department of Home Affairs, ‘Temporary work (skilled) visa program’, October 21 2024, accessed January 29 2025 <https://data.gov.au/dataset/ds-dga-2515b21d-0dba-4810-afd4-ac8dd92e873e/details>.

43. Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Labour force, Australia’, January 16 2025, accessed January 29 2025 <https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-australia/latest-release>.

44. Migration Council of Australia, ‘Treaties Committee inquiry: Submission by the Migration Council of Australia’, Joint Standing Committee on Treaties, Parliament of Australia, July 2015 <https://www.aph.gov.au/DocumentStore.ashx?id=752356d7-5d9b-43b0-ad75-ca873632455d&subId=355179>.

45. Brendan O’Connor, ‘Working to support local workers’, The Australian Financial Review, June 12 2013.

46. Michaelia Cash, ‘IMMI 13/17 - Specification of occupations exempt from labour market testing’, Federal Legislation of Government, Australian Government, November 18 2013 <https://www.legislation.gov.au/F2013L01952/asmade/text>.

47. Michaelia Cash, ‘IMMI 14/107 – Determination of international trade obligations relating to labour market testing’, Federal Legislation of Government, Australian Government, November 6 2014 <https://www.legislation.gov.au/F2014L01510/asmade/text>.

48. Australian Government Department of Home Affairs, ‘Temporary work (skilled) visa program’, October 21 2024, accessed January 29 2025 <https://data.gov.au/dataset/ds-dga-2515b21d-0dba-4810-afd4-ac8dd92e873e/details>.

49. Joanna Howe, ‘The impact of the China-Australia free trade agreement on Australian job opportunities, wages and conditions’, University of Adelaide, October 6 2015 <https://apo.org.au/node/57710>.

50. Australian Government Department of Home Affairs, ‘Nominating a position – Labour market testing’, accessed January 29 2025 <https://immi.homeaffairs.gov.au/visas/employing-and-sponsoring-someone/sponsoring-workers/nominating-a-position/labour-market-testing>.

51. Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ‘Information note on movement of natural persons provisions’, August 17 2015 <https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/chafta/news/Pages/information-note-on-movement-of-natural-persons-provisions>.

52. Joanna Howe, ‘The impact of the China-Australia free trade agreement on Australian job opportunities, wages and conditions’, University of Adelaide, October 6 2015 <https://apo.org.au/node/57710>.

53. Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ‘Memorandum of Understanding on an Investment Facilitation Arrangement’, June 17 2015 <https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/chafta/official-documents/Pages/official-documents>.

54. Joint Standing Committee on Treaties, ‘Treaty tabled on 17 June 2015’, Official Committee Hansard, Parliament of Australia, September 7 2015 <https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Hansard/Hansard_Display?bid=committees/commjnt/29036158-7cb1-437e-bff4-0ab8af50f86d/&sid=0004>

55. Australian Government Department of Home Affairs, ‘Temporary Work (skilled) visa program’, October 21 2024, accessed January 29 2025 <https://data.gov.au/dataset/ds-dga-2515b21d-0dba-4810-afd4-ac8dd92e873e/details>.

56. Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ‘Australia’s direction of goods and services trade – financial years from 2006-7 to present’, accessed March 3 2025 <https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/trade-and-investment-data-information-and-publications/trade-statistics/trade-time-series-data>; Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ‘Trade statistical pivot tables’, accessed January 29 2025 <https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/trade-and-investment-data-information-and-publications/trade-statistics/trade-statistical-pivot-tables>; Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘International trade: Supplementary information, financial year’, December 12 2024 <https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/international-trade/international-trade-supplementary-information-financial-year/latest-release>.

57. Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ‘Australia’s trade in goods and services by top 15 partners’, accessed February 28 2025 <https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/trade-and-investment-data-information-and-publications/trade-statistics/trade-in-goods-and-services/australias-trade-goods-and-services-2023-24>.

58. James Laurenceson, ‘Australia’s narrative on Beijing’s economic coercion: context and critique’, in Mabo Gao, Justin O’Connor, Baohui Xie and Jack Butcher, eds., Different Histories, Shared Futures: Dialogues on Australia-China (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023).

59. Katharine Murphy, ‘Turnbull told to ‘discard prejudice’ as China denies interfering in domestic affairs’, The Guardian, December 6 2017 <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/dec/05/turnbull-told-to-discard-prejudice-as-china-denies-interfering-in-domestic-affairs>.

60. Jennifer Hewett, Michael Smith and Phillip Coorey, ‘China puts Malcolm Turnbull’s government into the deep freeze’, The Australian Financial Review, April 11 2018 <https://www.afr.com/world/asia/chinas-big-chill-for-australia-20180411-h0ymwb>.

61. Michael Slezak and Ariel Bogle, ‘Huawei banned from 5G mobile infrastructure rollout in Australia’, ABC News, August 23 2018 <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-08-23/huawei-banned-from-providing-5g-mobile-technology-australia/10155438>.

62. James Curran, ‘Morrison’s ‘longest night’: Inside the making of AUKUS’, The Australian Financial Review, July 1 2024 <https://www.afr.com/policy/foreign-affairs/morrison-s-longest-night-inside-the-making-of-aukus-20240630-p5jpuo>.

63. Joe Kelly, ‘Scott Morrison says Labor must embrace AUKUS as a military deterrent against China’, The Australian, December 8 2024 <https://www.theaustralian.com.au/world/scott-morrison-says-labor-must-embrace-aukus-as-a-military-deterrent-against-china/news-story/eae8044bebca092488770b9543504ef4>.

64. ‘In conversation with Senator the Hon Simon Birmingham’, Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney, October 17 2024 <https://www.uts.edu.au/acri/events/conversation-senator-hon-simon-birmingham>.

65. Stephen Dziedzic, ‘Federal government will not cancel Chinese company Landbridge’s Port of Darwin lease’, ABC News, October 20 2023 <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-10-20/port-of-darwin-chinese-company-lease-not-cancelled/103003452>.

66. Joe Kelly, ‘Defence ticks Chinese lease of Darwin Port’, The Australian, December 28 2021 <https://www.theaustralian.com.au/nation/politics/defence-ticks-chinese-lease-of-darwin-port/news-story/4aae7af9297d5979d9363fdcfdf124fc>.

67. Daniel Hurst, ‘Scott Morrison says he ran out of time to impose sanctions on China over human rights’, The Guardian, February 17 2023 <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/feb/17/scott-morrison-says-he-ran-out-of-time-to-impose-sanctions-on-china-over-human-rights>.

68. ‘In conversation with Senator the Hon Simon Birmingham’, Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney, October 17 2024 <https://www.uts.edu.au/acri/events/conversation-senator-hon-simon-birmingham>.

69. Rowan Callick, ‘Australia’s China debate is changing – we can’t allow ‘stability’ to distract us from Xi’s anti-West goals’, The Australian, October 24 2024 <https://www.theaustralian.com.au/commentary/australias-china-debate-is-changing-we-cant-allow-stability-to-distract-us-from-xis-antiwest-goals/news-story/26e1f6fc4fad4decb425b16af6bb6388>.

70. James Laurenceson, ‘Just how “naïve” and “fuzzy” is the Albanese government’s approach to China?’, Australian Outlook, Australian Institute of International Affairs, November 12 2024 <https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/australianoutlook/just-how-naive-and-fuzzy-is-the-albanese-governments-approach-to-china/>.

71. ‘In conversation with Senator the Hon Simon Birmingham’, Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney, October 17 2024 <https://www.uts.edu.au/acri/events/conversation-senator-hon-simon-birmingham>.

72. Ye Xue, ‘China’s economic sanctions made Australia more confident’, The Interpreter, Lowy Institute, October 22 2021 <https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/china-s-economic-sanctions-made-australia-more-confident>.

73. James Laurenceson and Shiro Armstrong, ‘Learning the right policy lessons from Beijing’s campaign of trade disruption against Australia’, Australian Journal of International Affairs, 77(3) (2023), pp. 258-275.

74. Don Farrell, ‘New year, new trade opportunities for Aussie agriculture’, media release, January 2 2024 <https://www.trademinister.gov.au/minister/don-farrell/media-release/new-year-new-trade-opportunities-aussie-agriculture>.

75. World Trade Organization, ‘China – Anti-dumping and countervailing duty measures on barley from Australia’, August 24 2023 <https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/SS/directdoc.aspx?filename=q:/WT/DS/598R.pdf&Open=True>.

76. Andrew Tillett, Michael Smith and Campbell Kwan, ‘Hopes rise for end to China trade bans after barley tariff deal’, The Australian Financial Review, April 11 2023 <https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/china-to-review-tariffs-on-australian-barley-20230411-p5czjx>.

77. Don Farrell and Murray Watt, ‘Statement on reinstatement of barley exporters to China’, joint statement, August 9 2023 <https://www.trademinister.gov.au/minister/don-farrell/media-release/statement-reinstatement-barley-exporters-china>.

78. Penny Wong, ‘Press conference with Don Farrell’, August 4 2023 <https://www.foreignminister.gov.au/minister/penny-wong/transcript/press-conference-don-farrell>.

79. Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, ‘ChAFTA Committee meetings’, accessed January 29 2025 <https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/chafta/news/implementation/chafta-committee-meetings>.

80. ‘Free trade agreement with China’, Essential Research, November 25 2014 <https://essentialvision.com.au/free-trade-agreement-with-china-2>.

81. ‘Aussies give stamp of approval to Australian-made goods’, Roy Morgan, January 29 2019 <https://www.roymorgan.com/findings/aussies-give-stamp-of-approval-to-australian-made-goods>.

82. Dan Conifer, ‘Free trade agreement: Voters oppose China-Australia deal after hearing controversial elements: poll’, ABC News, June 24 2015 <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-06-24/voters-oppose-china-australia-fta-due-to-controversial-elements/6568210>.

83. Simon Jackman, Gordon Flake et al., ‘The Asian Research Network | Survey on America’s role in the Indo-Pacific 2017’, United States Studies Centre, University of Sydney and Perth USAsia Centre, University of Western Australia, May 31 2017 <https://www.ussc.edu.au/the-asian-research-network-survey-on-americas-role-in-the-indo-pacific>.

84. Elena Collinson and Paul Burke, UTS:ACRI/BIDA Poll 2024: The Australia-China Relationship: What do Australians Think?, Australia-China Relations Institute, University of Technology Sydney, June 12 2024 <https://www.uts.edu.au/acri/research-and-opinion/polling/utsacribida-poll-2024>.