- Posted on 21 Aug 2025

- 4 minutes read

Australia’s offshore detention system is designed to be invisible. It operates out of sight, on distant islands, through outsourced contracts and bureaucratic language.

But behind the policies and politics are real people – people who have endured years of suffering in spaces built to isolate, punish and erase them.

The Weapons of Slow Destruction project was created to challenge this invisibility. Led by Thomas Ricciardiello and Darren Lee from the UTS Data Arena, in collaboration with philosopher Omid Tofighian and Iranian refugee Elahe Zivardar, the project exposes the impact of architecture on those detained in offshore detention centres, and poses the question: what does it mean to design a space for suffering?

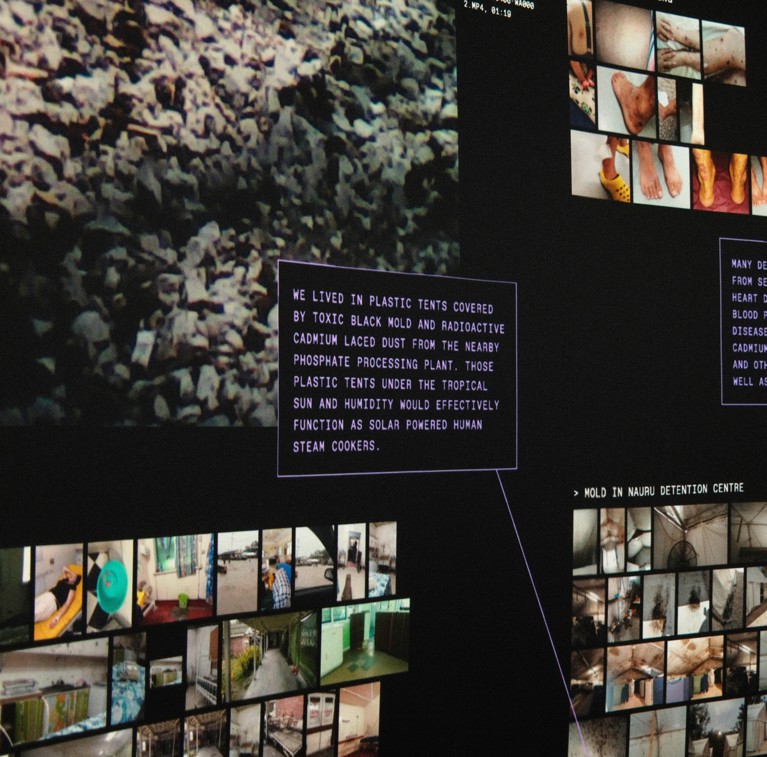

At the heart of the project is Elahe’s archive. Imprisoned on Nauru from 2013 to 2019, Elahe – an Iranian refugee – secretly documented her surroundings, capturing over 400 photographs, architectural drawings, maps, videos, diary entries and 3D model renders. Her material offers a rare, firsthand view of life inside Offshore Processing Centre 3 (OPC3), and the toll it takes on those held there.

‘This project is about truth-telling,’ says Ricciardiello. ‘It’s about showing how violence is embedded in space and how that space is used to control and dehumanise.’

Designing for creative and collaborative resistance

The Weapons of Slow Destruction project was developed through a deeply collaborative and organic process. Weekly meetings between the UTS Data Arena team, Omid Tofighian and Elahe Zivardar became spaces for open dialogue, emotional reflection and creative planning. The team didn’t begin with a fixed outcome – instead, they let the archive guide them.

‘We weren’t just creating a video,’ says Ricciardiello. ‘We were building trust and a space where Elahe’s story could be told with care, honesty and power.’

The final output was a 23-minute immersive video experience, presented in the UTS Data Arena. It transitions through several thematic lenses: design, space, identity and time, all while showcasing a large portion of Elahe’s archive. Annotations accompany the video, offering viewers a layered understanding of the detention centre’s design and its psychological impact.

A powerful public response

The exhibition launched in March 2025 with a public event attended by around 80 people. Additional sessions followed, reaching another 50–60 viewers. The Data Arena’s immersive format allowed audiences to engage with the material in a visceral, embodied way; surrounded by the sights and sounds of a space designed to isolate and control.

Audience feedback was immediate and emotional.

‘Emotionally and politically, it gave me a much closer engagement with the lived experiences of detained refugees,’ wrote one attendee. ‘The perspectives and feelings of children were especially impactful.’

‘It was a magnificent exhibition,’ said another. ‘I felt very immersed in the space of the camp and could really appreciate its size, monotonousness and profound hostility to supporting the conditions required for a flourishing life.

‘The way the message was delivered via media and the Data Arena was exemplary. It made me feel just as much as a full-length documentary I watched about Nauru,’ they said.

‘To see people connect with the material, not just intellectually, but emotionally, that’s what we hoped for,’ says Ricciardiello. ‘It’s not just about awareness. It’s about creative resistance and collaboration. It’s about calling individuals to take action.’

A platform for change

Since the exhibition, the team has received requests to present the work to student groups, advocacy organisations and policymakers. There are plans to adapt the experience for virtual reality, and to expand the archive to include stories from other detention centres.

There’s also growing interest in integrating the project into educational settings. Faculty members at UTS and local high schools have proposed workshops, reading groups and curriculum extensions that use the exhibition as a starting point for deeper conversations about justice, migration and human rights.

Elahe retains full access to the work and can exhibit it elsewhere. The team hopes the project will open new opportunities for her, and for others like her.

Resistance through art

Weapons of Slow Destruction is not loud. It doesn’t shout. But it stays with you.

It’s a reminder that systems of violence don’t always look like violence. Sometimes, they look like buildings. Sometimes, they look like silence.

And sometimes, they can be resisted – through storytelling, through collaboration, and through the courage to see what we’ve been taught to ignore.

The problem

Australia’s offshore detention system is deliberately designed to be invisible – operating on remote islands, through outsourced contracts and bureaucratic language. This invisibility masks the suffering of refugees detained in spaces built to isolate, punish, and erase. The psychological and architectural violence embedded in these environments remains largely unseen and unchallenged.

The response

The Weapons of Slow Destruction project was developed to confront this invisibility. Led by Thomas Ricciardiello and Darren Lee from the UTS Data Arena, in collaboration with philosopher Omid Tofighian and Iranian refugee Elahe Zivardar, the project uses immersive media to expose the impact of detention architecture. Central to the project is Elahe’s archive – over 400 items including photographs, drawings, maps, videos, and diary entries – documenting her 6 years imprisoned on Nauru.

What helped accomplish this?

The project was shaped through a collaborative, trust-based process. Weekly meetings between the UTS team, Elahe, and Omid fostered emotional reflection and creative planning. Rather than starting with a fixed outcome, the team allowed Elahe’s archive to guide the development. The result was a 23-minute immersive video experience presented in the UTS Data Arena, combining thematic storytelling with annotated visuals to encourage collaboration and new forms of creative resistance.

This project was also supported by the UTS Centre for Social Justice & Inclusion through a Social Impact Grant, as well as the National Justice Project who connected Omid with the Data Arena team.

What has changed as a result?

The exhibition received a powerful public response, with audiences deeply moved by the immersive portrayal of detention. It sparked emotional and political engagement, and inspired calls for action. Since its launch, the project has attracted interest from educators, advocacy groups, and policymakers. Plans are underway to expand the archive, adapt the experience for virtual reality, and integrate it into educational settings. Elahe retains full access to the work, ensuring her story continues to be shared and heard.